|

On the 29th of July, the day of Saint Theodore, Korčula’s patron saint

Text and photos by Davor Rostuhar, Croatian journalist and photographer

MOREŠKA – posljednji autentični mačevalački ples Mediterana

National Geographic Hrvatska, kolovoz 2009

Na kamenoj pozornici podno zidina staroga grada Korčule počinje svečana, svevremena drama. Crni kralj dovodi bulu, djevojku okovanu lancima i moli je da pođe za njega, nudi joj cijelo kraljevstvo, ali ona, časna, po cijenu života odbija sužanjstvo i slobodom se diči, hrabro mu se suprotstavlja vičući da njeno srce pripada bilom kralju, koji istom stupa na scenu sa svojom vojskom, praćen odrješitim ritmovima pedeseteročlanoga limenog orkestra. Crni kralj ne pristaje vratiti bulu gorostastnomu bilom kralju pa se zadijeva boj između dvije vojske. Crni i bili lepršavo lete kamenom pozornicom, odmjeravaju snage i napokon ukrštaju mačeve, batu morešku. Orkestar prati svaki njihov potez svečanim, dramatičnim tonovima. Iz kolapa u kolap, čina u čin, bitke u bitku, sukob dviju vojska, dobra i zla, buja i buja.

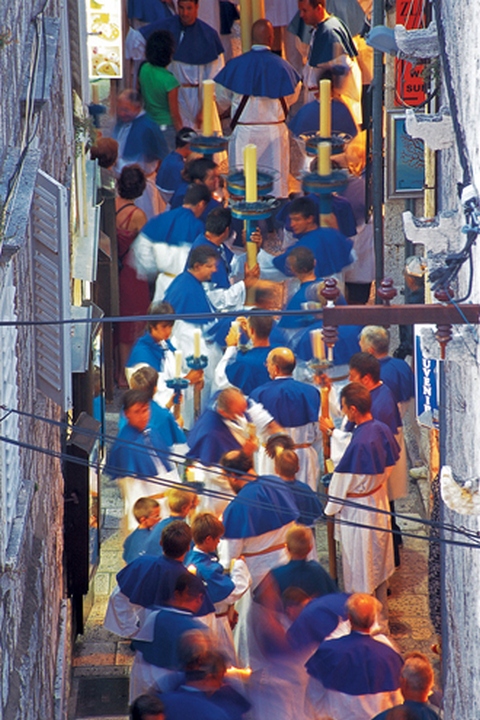

U publici tog dana sjede samo probrani Korčulani, žitelji staroga srednjovjekovnoga grada okružena zidinama. I oni koji se i dalje u zimske dane hrane usoljenom srdelom skrivajući se od bure u uskim ulicama poluotoka, i oni koji su se trbuhom za kruhom rasipali po cijelom svijetu. Svi se okupljaju na svojoj djedovini 29. srpnja, na dan svetog Todora, zaštitnika grada. Svaki je muškarac prije otišao k svojoj bratovštini, okitio se njenom insignijom i u velikoj svečanoj procesiji pronio svete relikvije kroz grad do crkve svetog Marka, katedrale koja se uzdiže poput osi usred poluotoka, na njegovoj najvišoj točki, upirući tornjem kao prstom u nebo.

“To se pije očima”, začujem nekog u publici kako komentira, očaran skladom izvedbe. Zaboravili su sad sve jer dočekali su morešku, najsvečaniji trenutak toga najsvečanijeg dana u godini. Jedinstvenu mediteransku mačevalačku igru koja se samo na Korčuli održala do današnjeg dana, središnju nit lokalnog identiteta. Ples koji se igra stotinu puta na godinu, za turiste i posjetitelje, ali koji se samo taj dan u godini igra isključivo za baštinike korčulanskog blaga. Oni već znaju svaki takt orkestra, svaki stih teksta i svaki pokret plesa, ali baš zato prepoznaju nijanse i vide promjenu, odstupanja, poboljšanja, individualne posebnosti i harmoniju kolektiva. Znalački upijaju svaki tren.

A bilima i crnima već su se čela zažarila na ljetnoj noći obasjanoj bakljama. S njih pršti znoj pri svakom udarcu. Lica se mršte, mačevi iskre, tu i tamo začuje se krik, netko je dobio po prstima. Nakon četvrtoga kolapa opet se upleće bula, moli momke da mirom okončaju stvar, no u njima se rasplamsao žar pa se bitka zapodijeva još jače u petom kolapu, još jače u šestome, još jače u sedmome. Mačevi lete s jednog vojnika na drugoga. Svaki se vojnik bori barem s dvojicom istodobno, ali njihovi se pokreti skladno izmjenjuju. Pod tempom glazbe tlače se do krešenda. Crni bivaju opkoljeni, na izmaku su snaga, gube, padaju, predaju se. Bili zastavnik vijori pobjedu, a bili kralj osvaja bulu i cjeliva je. Orkestar likuje, promalja se pljesak. No to nije znak za kraj rata ni igre, nego za početak slavlja.

|

MOREŠKA – The Last Authentic Sword Dance in the Mediterranean

National Geographic Croatia, August 2009

On the stone stage at the base of the city walls that encircle Korčula’s old town, an all-time ceremonial drama begins. A figure dressed in a black Baroque costume, the black king, brings forth the bula, a lady shackled in chains, and asks her to go with him. He offers her his entire kingdom, but she, being honorable, refuses to be his. For the price of her life, she bravely opposes him, proclaiming that her heart belongs to the white king. The white king, a figure dressed in a pompous white costume, then enters the scene with his army, accompanied by the steadfast rhythms of a fifty-member brass-band orchestra. The black king refuses to return the bula to the burly white king, and a battle between the two armies ensues. Blacks and whites leap about the stone stage, testing each others’ abilities and strengths. Until finally, the swords cross. The orchestra follows each movement with ceremoniously dramatic notes. From round to round, from rank to rank, battle to battle, a clash of two armies, good and evil, flourish.

Exclusively for this day, the audience is comprised only of Korčulans, inhabitants of this old medieval town bound by city walls. Of those who still consume salted anchovies through winter months and escape hurricane winds by retreating to the narrow streets of the peninsula; of those who have scattered throughout the world in search of a better living. They all gather in their grandfathers’ land on the twenty ninth of July, the day of Saint Theodore, Korčula’s patron saint. Each man had visited his fraternity earlier in the day, pinned his insignia on, and then carried holy relics in a procession through the city to Saint Mark’s Church, a cathedral that rises like a pillar in the peninsula’s center. Situated on this highest peak, it points its tower like a finger towards the heavens.

“A feast for the eyes,” says a voice from the public, enthralled by the performance. Thoughts about everything else are now all forgotten because The Moreška has arrived. For this is the most ceremonious moment of the most ceremonial day of the year. This unique Mediterranean sword dance, nurtured to this day only in Korčula, is the central tie of the town’s local identity. Held hundreds of times yearly for tourists and visitors, only on this day of the year is it performed exclusively for successors of Korčula’s wealth. They already know every measure the orchestra plays, every verse recited, and all the dance moves, but this is especially why they recognize the nuances and notice the changes, discrepancies, improvements, individual touches, and harmony of the collective. They professionally absorb every moment.

And in this summer eve, illuminated only by torchlight, the foreheads of the whites and blacks already shine. Droplets of sweat roll down their foreheads with each clash of the swords. They frown, swords spark, and every so often someone lets out a yelp, from having been hit. After the fourth round, the bula steps forth and asks the men to finish peacefully. But the seed of fire has already been set aflame, and the battle intensifies in the fifth round. Then more so in the sixth, and even more so in the seventh. Swords fly from one soldier to the other. Each soldier battles against at least two others at the same time, and their gestures alternate harmoniously. The orchestra increases its tempo, culminating to a crescendo, and the blacks find themselves surrounded, entrapped. They pull forth their last stretch of energy; they lose, fall, and surrender. As the white flag waves in victory, the white king takes the bula and caresses her. In exultation, the orchestra concludes its piece, and a grand applause by the audience follows. This, however, does not mark the end of the battle or of the game; rather it marks the beginning of the celebration.

|

Spuštaju se momci do kamenih prostorija u zidinama gdje je sjedište njihova društva. Grabe hladno pivo i, još zapuhani, odahnu.

“Kad sam pâ u sedmi kolap, ko da sam pâ u prsuru”, kaže jedan crni, s melodičnošću i mekoćom tipičnom za korčulanski dijalekt.

“Šuti, ja sam dobi po prstima, vidi krvi”, kaže drugi i pokazuje šaku na kojoj se krv već skorila. Svi nose neke uspomene na ozljede pri moreški. Pričaju mi tko je gdje zaradio koliko punata, odnosno šavova. Mlađi s ponosom usmjeravaju na svog učitelja moreške, 43-godišnjeg Žitomira iz obitelji Lozica, koja je izrodila ponajviše aktivnih moreškanata.

“Vidi Žitota, on je dobi posrid lica, između oka i nosa, zaradi punte.”

“Tišina, balavci,” progrmi nježno njihov omiljeni lik. “Koliko puta san van reka da ko je dobi (ozljedu), taj je kriv. Da ste dobro igrali, ne bi van ništa bilo!”

Momci su već skinuli odijela, graja raste, Korčulani se natiskavaju u skučene prostorije podno zidina. Galami se, veseli, zveckaju čaše i flaše. Vesela atmosfera gubi svoje konce.

“Ja san krvav, ja san znojan, bori san se za tebe”, dobacuje pijevno i lelujavo drugi ozlijeđeni mladić buli koja uto prolazi kraj njega. Ona se samo smije. Jedan stariji moreškant nadglasava graju i obraća im se s druge strane sobe.

“Nismo se mi borili za tu bulu, nego za one bule u publici!”

Razuzdana pijanka nadrasta te prostorije pa galamdžije odlaze do konobe. Kako prolaze kroz grad, ljudi se razmiču, turisti fotografiraju njihovo veselje. Ne podsjeća ta scena na časne vitezove iz turističkih prospekata. Stariji, ipak nešto mirniji moreškant Vojo Škrabec, koji promatra i komentira tu scenu sa strane, objašnjava mi: “Nismo se mi ništa prominili od početaka. Znaš da je prvi zapis moreške na Korčuli 1666. godine, kad smo završili kod kneza na sudu, zbog incidenta na karnevalu? Izazivali smo nevoje, uvridili neka tri ugledna Korčulana. Ali oprosti nan je knez, znaju svi kakvi smo. I drugi zapis 1685. godine opet spominje izgred koji su izazvali moreškanti. Eh, da nismo pravili nevoje, ne bi se ni znalo otkad postojimo.”

|

The men retreat to a stone room within the city walls, their association’s center, and grab some cool beers. Still flushed and out of breath, they now sigh with relief.

“When I fell in the seventh round, I felt as if I fell in the frying pan.” says one of the blacks with a melody and softness typical for the Korčulan dialect.

“That’s nothing; I got whipped, see the blood” the other shows the palm of his hand where the blood has already dried. They all hold memories of wounds gained during the moreška, and tell me stories about who got how many stitches, and where. The younger ones proudly lead me to their moreška master, fourty three year old Žitomir. He comes from a family that has raised the greatest number of active moreškants, the Lozica family.

“See Žitomir, he got cut right in the middle of his face, between his eye and nose, he got stitches.”

“Silence, kids,” Their favorite guy softly thunders. “How many times have I told you that if you get wounded, you’re the ones to blame. Had you played well, nothing would have happened to you!” The boys have already taken their costumes off, the commotion rises, Korčulans pack into the small rooms at the base of the city walls. They shout and cheer, glasses and bottles clink. A lively atmosphere unravels.

“I’m bloody, I’m sweaty, I fought for you,” another wounded young man woos with a songlike voice as the bula passes by him. She just laughs. One of the older moreškants shouts louder than the crowd, and addresses them from the other end of the room.

“We didn’t fight for that bula, we fought for the bulas in the audience!”

The unbridled drinking party outgrows the cosntraints of these rooms, and the unruly crowd heads for the tavern. As they pass through the town, people step aside to make way for them, and tourists photograph their merry parade. This scene is nothing like that of the honorable knights found in tourist prospects. The older, more composed Vojo Škrabec watches from the sidelines and comments this scene, explaining, “We haven’t changed a bit from the beginning. You know, the first written record about the moreška in Korčula was in 1666, when we ended up in the duke’s court, because of an incident in the carnival? We caused trouble; we offended some three notable Korčulans. But the duke forgave us, everyone knew how we were. The second record was in 1685, where another mess was made by the moreškants. Oh, if we hadn’t made trouble, no one would have known how far back our existence goes.”

|

A moreška je na Korčuli sigurno i dulje jer taj prvi zapis u aktu korčulanskoga kneza Paula Paskvaliga daje naslutiti da je moreška tad bila već uhodana stvar i živo tkivo korčulanskog društva. No dokle točno sežu korijeni moreške, ne zna se točno. Prema jednoj teoriji, moreška je nastavak plesa iz prastarih vremena, plesa starih Grka. Druga verzija kaže da su korčulanski zanatlije morešku naučili od đenovskih mornara za vrijeme đenovskoga gospodstva nad Korčulom u 12. i 13. stoljeću. Treći pak kažu da je igra bez sumnje španjolskog podrijetla. Da je zapravo riječ o rekonkvisti, ponovnomu kršćanskom osvajanju Pirenejskog poluotoka nakon što su njime više stoljeća gospodarili Mauri. Uostalom, etimološki ‘moreška’ najvjerojatnije i dolazi od riječi Maur, Mor. Ta se teorija ponajviše uvriježila u narodu. Prema njoj se moreška prvi put igrala u španjolskoj Leridi sredinom 12. stoljeća, kao prisjećanje na protjerivanje Maura. Potom se proširila cijelim Mediteranom, a u Korčulu je došla preko južne Italije i Dubrovnika u 16. stoljeću.

S tim se ne slaže Elsie Ivancich Dunin, profesor emeritus kalifornijskog sveučilišta UCLA i suradnik Instituta etnologije i folkloristike u Zagrebu. Ta ugledna etnokoreologinja hrvatskih korijena, nakon što je odradila upečatljivu akademsku karijeru u Sjedinjenim Državama, vratila se u Hrvatsku i počela proučavati morešku i druge mačevalačke igre na Korčuli te je trenutačno ponajveći autoritet za korčulansku morešku u svijetu. Ona tvrdi da je u 15. i 16. stoljeću u Europi postojalo toliko različitih varijacija mačevalačkih plesnih igara s temom borbe kršćana protiv Maura da je teško potvrditi kontinuitet korčulanske moreške zbog manjka detaljnih informacija. Slične su se igre čak proširile i američkim kontinentom nakon španjolskog osvajanja Novog svijeta.

“Ja pretpostavljam te istražujem varijantu da je moreška došla na Korčulu iz Venecije najkasnije početkom 17. stoljeća”, otkriva mi umirovljena profesorica koja većinu vremena provodi u Zatonu pokraj Dubrovnika. “Kad se spremala velika bitka kod Lepanta 1571. godine, Mlečani su sa svojih teritorija zaposlili stotine vještih radnika, a Korčulani su bili poznati brodograditelji. Ti su se ljudi držali skupa u cehovima, ženili međusobno i kumili. U Veneciji su pak pripadnici svih cehova morali sudjelovati u čestim prazničkim ceremonijama, gdje se vrlo vjerojatno prakticirala i moreška. Pretpostavljam da su tamo Korčulani naučili morešku i potom je donijeli na Korčulu.”

|

But the moreška in Korčula definitely dates further back, because the first written record, by Korčula’s duke Paul Paskvalig, insinuates how the moreška had by then already been a well established and substantial part of Korčula’s society. How far back the moreška’s roots reach, is not known exactly. According to one theory, the moreška is a sequel to a dance from ancient times, to a dance of the ancient Greeks. Another version claims that Korčulan tradesmen learned the moreška dance from Genoa’s sailors during Genoa’s rule over Korčula in the 12th and 13th centuries. A third theory, though, claims this play originates from Spain. That it tells the tale of the re-invasion, the second Christian conquest of the Iberian Peninsula after many centuries of rule by the Moors. Furthermore, the word “moreška” most likely etymologically derives from the word Maur, or Mor. According to this theory, which is the most widely spread among the people, the moreška was first danced in Spanish Lerida in the middle of the twelfth century in honor of the victory over the Moors. It then spread throughout the Mediterranean, and came to Korčula by way of Italy and Dubrovnik in the sixteenth century.

Elsie Ivancich Dunin, professor emeritus at the University of California in Los Angeles and associate at the Institute of Ethnology and Folklore Studies in Zagreb, agrees with this theory. After having built a respectable academic career in the United States, this notable ethno choreologist of Croatian descent came to Croatia to study the moreška and other sword games in Korčula, and is now the greatest authority for Korčulan moreška in the world. She explains how there were so many different variations to the sword dance plays based on the battle of Christians against Moors, that the lack of detailed information makes it difficult to confirm the continuity of the Korčulan moreška. Similar plays even spread across the American continent during Spanish colonization of the New World.

“I suppose and research the possibility that the moreška came to Korčula from Venice at the latest in the beginning of the seventeenth century,” says the retired professor who spends most of her time in Zaton near Dubrovnik. “When they prepared for a great battle at Lepant in 1571, the Venetians employed hundreds of skilled workers from their territories, and the Korčulans were known for their shipbuilding skills. These people kept together in guilds, started families among each other, and further strengthened these bonds through godparent relations in religious sacraments also. In Venice, members of all guilds had to participate in frequent holiday ceremonies, where they most likely participated in the moreška. I suppose that the Korčulans learned the moreška there, and then brought it to Korčula.”

|

Društvo je na otoku kroz novi vijek bilo jasno raslojeno. U unutrašnjosti su se ljudi bavili poljoprivredom i manje stočarstvom, a Korčula je bila jedini obalni grad, opasan zidinama i razvijen. Svaka utjecajna obitelj na otoku imala je svoju kuću unutar zidina Korčule. Tu su ljudi uglavnom bili tesari i kovači pri brodogradnji te kamenoklesari i ribari. Profesorica Ivancich Dunin kaže kako su morešku mogli igrati brodograditelji, snažni ljudi. “U jednom listu krajem 19. stoljeća objavljen je popis imena moreškanata, a ja sam doznala da su gotovo svi pripadali brodograditeljskim obiteljima. U crkvenim spisima pratila sam njihove genealogije natrag u povijest sve do polovine 16. stoljeća, otkad postoje bilješke.” Iako još nije pronašla dokumente koji bi to potvrdili, profesorica Ivancich pretpostavlja da su korčulanski brodograditelji tada radili upravo u Veneciji.

Drugi još nerazriješen problem jest taj što se samo na Korčuli u moreški protiv Maura bore Turci, a ne kršćani. Bili kralj ovdje je Osman, a bula je Turkinja, što i dan-danas zbunjuje mnoge promatrače, pa čak i neke Korčulane. “Znamo da su 1846. godine korčulanski brodograditelji nastupili u Istanbulu”, objašnjava profesorica, koja i za to ima svoju teoriju. “Oni su tad pripadali Austriji, a jasno je kakvi su tad bili odnosi bečkog i carigradskog dvora. Korčulanima vjerojatno nije bilo ugodno usred Osmanskog Carstva nastupiti s igrom u kojoj kršćani pobjeđuju muslimane pa pretpostavljam da su Turke stavili u pogodnu ulogu bilih, a nekadašnju schiavu prozvali bula.”

Početkom dvadesetog stoljeća moreška se izvodila rijetko, a za vrijeme svjetskih ratova zamrla je na neko vrijeme. Godine 1944. počelo je novo doba korčulanske moreške i njen uzlet u dotad neslućene visine.

“Ja san jedini živi ko je nastupi te godine u Hvaru”, sjeća se 79-godišnji Kruno Lozica, a pogled mu otpiri u daljinu, zamišljeno i sjetno, dok sjedi na klupi ispred svoje kamene kuće pod zidinama staroga grada. “A nisan, ima još jedan...”, trgne se odjednom, a odmah potom ponovno izgubi negdje u daljini, “ali on se više ne miče”, kaže pa me pogleda, nasmije se prepredeno, a oči mu se zacakle na tren.

Kruno je iz velike moreškantske obitelji. Čak devetero braće i jedna sestra, svi su bili uključeni u rad Kulturnog društva “Moreška”, bilo kao moreškanti bilo kao mužikaši. Njihov je otac Ivo Lozica zaslužan za oživljavanje moreške pred kraj Drugoga svjetskog rata. “Odijela su nam nestala u ratu”, nastavlja šjor Kruno, “pa smo otišli u crkvu do padre Bernarda, koji je skapava od gladi. Dali smo mu hranu što su je nama dali vojnici, a on je nama dâ crnu i crvenu tkaninu s oltara da sašijemo veštite.” Nakon rata moreška se igrala sve češće, sjeća se šjor Kruno. “Batilo se na svetega Todora, za posjetu nekih velikih državnika i za brodove. Njih je u početku bilo tri-četiri godišnje, ali s vrimenom sve više.”

Sjeća se Kruno i kako su se određeni elementi moreške mijenjali pod pritiskom određenih vladara. “Zastavnici nisu imali punpuna, nego fes, a na zastavi su bili zvizda i misec, ali makli smo sva nacionalna obilježja. Kad je doša Tito, reka nan je da što crni pituraju lice u crno, da to ni lipo, pa smo prestali, ipak je on bi vođa nesvrstanih. A i prominili smo tekst, nismo se više obraćali hudom Arapinu, nego dušmaninu. No bulin tekst se nî minja”, ponovno mu usne zaigraju, a obrve poskoče, “njen je pojubac isto sladak i onda i sada.”

|

Society on the island through the new era was clearly layered. In the inlands, people were farmers and small scale ranchers. Korčula was the only coastline city, confined by city walls, and developed. Every influential family on the island owned a house within the city walls of Korčula. These people were mainly carpenters and blacksmiths for shipbuilding, and stone carvers and fishermen. Professor Ivancich Dunin further explained how the moreška could have been played by shipbuilders, who were muscular and artful people. “The names of moreškants were listed in one paper towards the end of the nineteenth century, and I found out that almost all of them belonged to shipbuilder families. I traced their genealogies in documents from the church all the way back in history to the mid sixteenth century, which is how far back these files go.” Although she still hasn’t found the documents that could confirm this, professor Ivancich believes that the Korčulan shipbuilders worked particularly in Venice.

Another unsolved problem is the fact that only in the Korčulan Moreška, are the battles against the Moors fought by Turks, and not Christians. The white king here is Osman, and the bula is a Turkish lady, which to this day confuses many spectators, and even some Korčulans. “We know that in 1846, Korčulan shipbuilders performed in Istanbul,” the professor explains her theory about this, “At that time they belonged to Austria and it is clear to us now how the relationship between Vienna and Constantinople was back then. Venetians probably did not feel comfortable performing in the midst of the Osman Empire a play in which Christians defeated Muslims, so I suppose they proclaimed the white soldiers as Turks, and they made the schiava of those times the bula.”

Towards the beginning of the twentieth century, the moreška was not performed often, and during the world wars, it died out. In 1944, a new era began for the the Korčulan moreška, and its popularity rose to unimaginable heights.

“I am the only one still alive who had performed in Hvar that year,” remembers seventy nine year old Kruno Lozica. He nostalgically gazes into the distance while seated on a bench in front of his stone house by the old town’s city walls. “Oh I’m not, there’s one more…” he wakes up for a moment, then immediately retreats into the distance, “but he cannot move anymore.” He looks at me, smiles elusively, and his eyes shine for a moment.

Kruno comes from a great moreška family. All nine of his brothers and sisters had participated in the cultural association “Moreška”, either as moreškants or as musicians. Credit for bringing the moreška back to life towards the end of World War II goes to their father, Ivo Lozica. “Our costumes disappeared during the war,” mister Kruno continues, “So we went to the church to see Father Bernard, who was starving to death. We gave him food that the soldiers had given to us, and he gave us black and white cloth from the altar to sew costumes.” After the war, the moreška was played more often, mister Kruno remembers. “We battled on Saint Theodore’s day, when great statesmen visited, and for ships. In the beginning, that was about three to four times yearly, but with time we performed more and more.”

Kruno remembers how certain elements of the moreška changed under pressure of certain leaders. “The flag bearers wore a fez and there was a star and moon on the flag, but then they had the national symbols removed. When Tito came, he asked why the blacks paint their faces black, and said that that’s not nice, so we stopped doing that. After all, he was the leader of the Non-Aligned. And we changed the text; we didn’t address the evil Arabs, but the enemy instead. But the bula’s text did not change,” he smiles with a twinkle in his eyes, “her kiss is as sweet now as it was back then.”

|

Zbog sve češćeg dolaska turista na Korčulu porasla je i potreba za više moreškanata i više bula. Sve je više mladića bilo aktivno uključeno u rad Kulturnog društva “Moreška”, ali je ona unatoč sve većem priljevu financijskih sredstava ostala strogo amaterska. Neke su tenzije unutar društva ipak narasle pa se početkom devedesetih dogodio presedan u povijesti moreške – iz društva se odcijepila jedna grupa koja je nastavila igrati morešku unutar udruge “Sveta Cecilija”. I jedno i drugo društvo vrednuje isto socijalno pravilo, da morešku može igrati samo onaj kojem je barem jedan roditelj iz Korčule. Njihove su izvedbe gotovo iste, iako jedni drugima zamjeraju štošta. Članovi “Moreške” zamjeraju cecilijancima što plaćaju sto kuna po nastupu svojim moreškantima, tvrdeći da su time izgubili amaterizam. Kažu im da igraju mirnije i elegantnije, da im mačevi ne iskre. S tim se cecilijanci, naravno, ne slažu, jer s istim žarom pristupaju svome kulturnom naslijeđu, čak ističu kako su vratili promjene poput bojenja lica crnom bojom i teksta “Hudi Arapine...”. Cecilijanci kažu i da su istupili iz društva “Moreška” jer je obitelj Lozica “privatizirala” morešku i preuzela cijelu stvar u svoje ruke.

No ono što ih je u posljednjih nekoliko godina ponovno zbližilo jest činjenica da je morešku kopirao Lado, profesionalni folklorni ansambl iz Zagreba. Ogorčeni Korčulani uzbudili su se i dignuli na noge, jedinstveni u svojoj pobuni, izjavljujući da je to čin agresije na njihovo kulturno dobro, njihovu tradiciju i njihov grad. “Moreška izvan Korčule i moreškanata tek je vulgarna komercijalna kopija koja duboko vrijeđa naše najdublje osjećaje i zadaje smrtnu ranu našoj stoljetnoj baštini”, izjavili su građani u skupnom pismu svim visokim državnim institucijama, otkrivajući pritom samu bit moreške. “Lado nam može oteti robu, mačeve, naručiti i platiti drugu glazbu, ali ne može nam oteti dušu, a bez duše se moreška ne može batiti... Uostalom, na kamenu ovoga škoja smo i opstali zato što smo stoljećima čuvali i očuvali svoju kulturu, tradiciju, povijest i dostojanstvo.” Istaknuti Korčulani potcrtali su da se moreška ne može “doživjeti pukim promatranjem jer ona nije igrokaz, nego briljantni iskaz simbioze igrača – moreškanata, sudionika – građana i ambijenta – Korčule”.

Jedini kontraargument koji im je Lado ponavljao – njihov stav da je baština previše važna da bi bila prepuštena samo baštinicima – naišao je na još veće ogorčenje Korčulana. Kruno Lozica prokomentirao mi je to vidljivo uzbuđen: “A ko, molin te, može boje sačuvat morešku od nas samih? Pa mi smo je jedini sačuvali sve ovo vrime, dok je svugdi drugdi po Mediteranu nestala.”

|

The increasing number of tourists in Korčula has created a greater demand for moreškants and bulas. More and more youths started participating in activities of the cultural association “Moreška”. However, despite this increase in profits, the association has remained strictly amateur. Some tension had risen within the association and towards the beginning of the nineteenth century, when a benchmark in the history of moreška occurred: a group separated and continued performing the moreška as part of the association “Saint Cecilia”. Both associations follow the same principals: the moreška can be played only by those for whom at least one parent is from Korčula. Their performances are pretty much the same, although they find many faults in one another. Members of “Moreška” are angry at the “Cecilians” for paying a hundred Croatian kunas per performance of their moreškants, claiming that by doing this, they have lost their amateurism. They further claim how the “Cecilians” play more peacefully, with more elegance, and that their swords do not spark. The “Cecilians”, of course, do not agree, because they perform with an equal passion for their cultural inheritance. Moreover, the “Cecilians” even emphasize how they have revived the old customs, such as face-painting of the blacks and use of the texts “Evil Arabs…” They claim they have separated from “Moreška” because the Lozica family “privatized” it by taking things into their own hands.

But what has brought them closer again these past few years is the fact that the professional folklore ensemble from Zagreb, “Lado”, copied the moreška. Angered Korčulans rose in defiance, unified in their rebellion, claiming that that is an act of aggression towards their cultural wealth, their tradition, and their city. “Moreška outside of Korčula and without moreškants is merely a vulgar commercial copy that deeply insults our deepest feelings and inflicts a deadly wound to our centuries old heritage,” the citizens said in a letter they had written to all ranking government institutions, thus revealing the very meaning of the moreška. “Lado can steal our clothes, swords, they can order and pay for other music, but they cannot take our soul, and without soul a moreškant cannot play... Besides, we have survived on these stones because for centuries we have kept and nurtured our culture, our tradition, history, and dignity.” Eminent Korčulans emphasized that moreška cannot “be experienced just by observing because it is not a play, rather it is a brilliant expression of the symbiosis of play-moreškant, participant-citizens, and ambient-Korčula.”

One of the counterarguments that Lado repeats – their opinion that the heritage is too important to be left only to its inheritors – was taken with even more bitterness by the Korčulans. Kruno Lozica commented this to me with a clearly excited tone, “And who, please say, can better preserve moreška than us alone? We were the only ones that preserved it the whole time, while everywhere else in the Mediterranean, it disappeared.”

|

Na pitanje zašto je moreška opstala toliko dugo baš i samo na Korčuli, teško je odgovoriti. Profesorica Ivancich Dunin kaže da je riječ o slučajnosti. No možda je odgovor u elementima snažne društvene kohezije. Isto kao što kulama učvršćene zidine skladno na okupu drže krovove staroga grada, tako na okupu drže i ljude koji žive ispod tih krovova. Oni su sami od davnih dana pronašli načine da se snažno povežu – udruživši se u bratovštine. I danas u Korčuli djeluju tri bratovštine – gotovo svaki muškarac član je jedne od njih.

Najstariju bratovštinu Svih svetih osnovali su još 1301. godine. Kad je Korčulu poharala kuga, osnovali su još jednu, svetog Roka, 1575. godine, u zavjet Bogu da ih oslobodi te pošasti. Ta je danas najbrojnija. Najmlađa bratovština svetog Mihovila, odnosno Gospe od Utjehe, osnovana je 1603. godine i najbogatija je po fondu svijeća. Na najvećim procesijama na Veliki petak, Tijelovo ili za svetog Todora stotine mihovilaca nose goleme svijeće, koje su ponekad teške i do osamdeset kilograma.

Bratovštine su prije sličile cehovskim udrugama, pomagale bi siromašnima, bolesnima, potrebitima, udovicama. One okupljaju ljude prije svega zbog pobožnosti prema njihovim svecima zaštitnicima, ali i neovisno o tome. Za vrijeme socijalističke Jugoslavije mnogo ljudi nije se krstilo, ali je redovito sudjelovalo u životu bratovštine. Jer, svaki se Korčulan rođenjem nađe u jednoj od tri bratovštine koje i danas drže Korčulane na okupu. Kao što mi Kruno Lozica kratko i jasno reče: “Svi smo mi mogli bit svugdi po svitu, ali Korčula je Korčula.”

Možda je upravo zahvaljujući bratovštinama i dišpetu stanovnika slikovitoga grada moreška preživjela samo na Korčuli. Ali ona ne živi samo na kamenoj pozornici za svetog Todora, nakon što bratovštine svečano ophodaju gradom, nego i u pozadini svakog dana. Sastajem se s moreškantima u konobi jedne obične večeri radnog dana, kad nisu igrali morešku, ali su se svejedno okupili u velikom broju. Tek je krenulo vino iz bukare oko stola, ali atmosfera je već glasna i vesela. Na čelu debeloga drvenog stola sjedi 48-godišnji Toni Lozica, sredovječni muškarac impozantne pojave, visok više od dva metra, snažan, lepršave bijele košulje, duge bijele kose i uredne bijele brade. Figura mu doista podsjeća na kraljevsku. “Sad ćeš ti vidit što je zapravo moreška”, smije se i progovara gromoglasno. “Ovi u turističkim prospektima kažu da smo vitezovi, ali jedino što je kod nas viteško jest to što smo svi za jednoga i jedan za sve. Mi nismo plemenite krvi, mi smo obični manovali”, kaže s kraljevskom skromnošću iako je sâm menadžer najskupljeg hotela palače među zidinama staroga grada. Za stolom sjede i stari i mladi, i bogati i siromašni, a bili kralj Toni nastavlja. “Mi morešku ne plešemo, mi je batimo! To je borba, to je muška stvar, borba za divojku, oplodnja, produljenje vrste...” Svi se već kidaju od smijeha, ali kimaju u znak odobravanja. “To je vječna stvar”, kaže Toni. “Da je bilo išta političko ili religijsko u moreški, ne bi ona opstala sve ove godine.”

|

To the question why the moreška survived so long just and only in Korčula, is not easy to answer. Professor Ivancich Dunin says that it is by chance. But the answer may lie in the elements of tight social cohesion. Just as the roofs of the old town are rounded together, embraced by the city walls and towers, the people who live under these roofs nurture close ties with one another. For long ago have they found the way to keep tightly connected: through membership in fraternities. Even today three fraternities exist – and almost every man is a member of one of them.

The oldest, The Fraternity of All Saints, was founded back in 1301. When the black plague swept over Korčula, another was founded, Saint Roko, in 1575 as an oath to God in order for Him to free them of the plague. Nowadays, this one has the most members. The youngest fraternity, Saint Mihovil, or Our Lady of Comfort, was formed in 1603, has the wealthiest fund in candles. During the greater processions, on Good Friday, Body of Christ day, or on Saint Theodore’s day, hundreds of Mihovilans carry huge candles, some of which weigh up to eighty kilograms.

The fraternities used to be more like guilds. They helped the poor, ill, needy, and the widowed. Earlier, people had primarily joined out of devotion to the patron saints of these fraternities, and later they joined despite them. During the time of socialist Yugoslavia, many people regularly participated in activities of the fraternity despite the fact that they had not been baptized. Basically, every Korčulan belongs to one of these three fraternities from birth, and this is what keeps Korčulans together today. As Kruno Lozica simply and clearly said, “All of us could go anywhere in the world, but Korčula is Korčula.”

It may be that the moreška survived only in Korčula precisely because of these fraternities and because of the spite of the inhabitants of this picturesque city. But it does not live only on the stone stage during Saint Theodore’s day, after the fraternities ceremoniously parade through the city, rather it lives in the background of everyday. The moreškants had gathered one weeknight in the tavern. Although they did not have a moreška performance that evening, they gathered in a great number nevertheless. The wine had just started circling around the table, and the atmosphere was already loud and cheerful. At the head of the table sat forty-eight year old Toni Lozica, a stately middle aged man, more than two meters tall, muscular, wearing a loose white shirt, with long white hair and a neat white beard. His stature truly reminded me of royalty. “Now you will see what moreška really is,” he laughs and thunders as he speaks up. “These tourist leaflets say that we are knights, but the only knightly thing about us is that we are all for one and one for all. We do not have royal blood. We are just ordinary workers” he says with a royal modesty, although he himself is the manager of the most expensive palace hotel the old town’s city walls. Both young and old sit at the table, both poor and rich, and Toni the white king continues. “We don’t dance the moreška, we fight it! It’s a battle; it’s a male thing, battle for a girl, fertilization, passing down our genes…” They are all rolling with laughter by now, but also nodding their heads in approval. “This is a timeless matter,” Toni says, “Had there been anything political or religious in the moreška, then it wouldn’t have survived all these years.”

|

Vesela zabava traje i kasno nakon što su se vrata konobe službeno zatvorila, a ja promatram sve mladiće oko velikog stola i počinjem primjećivati razlike u njihovim karakterima. Ispitujem ponaosob tko igra bilog, a tko crnog, a Toni prozre moju nakanu. “Ni bezveze ko je bili, a ko crni!”, kaže.

Svi mi stanu objašnjavati da bili uglavnom moraju biti oni snažnije konstitucije, viši, umjetničke duše, filozofi... Crni kažu za bile da su mamine maze, naviknuli uvijek sve dobivati pa hoće pobjeđivati, ali priznaju da doista uvijek pobjeđuju, i u nogometu i potezanju konopa. Bili im vraćaju rekavši da su crni prgavi, da puno laju, da su buntovnici bez razloga, “luzeri”. Jedan se crni našao šaljivo uvrijeđen pa podigne glas.

“Bula više voli bitangu nego dobrog čovika, ko i svaka prava cura. Svi bili krajevi zavide crnima jer je crni kraj u predstavi sâm na sceni sa bulom pet minuti, a on nikad nî sâm s njom.” “Ali je on pojubi na kraju”, smije se jedan bili.

“E, pojubi je u obraz”, odvraća crni, “da mi kojin slučajen pobijedimo, pojubili bi je kako spada. Al’ dobro, neka ti je, u predstavi je ima bili, ali zato poslije predstave crni!” Smijeh se neprestano odbija od kamenih zidova konobe. Prekida veselu atmosferu ozbiljnim tonom Žitomir, crni kralj: “Najbolji primjer su ti mala dica. Kad su mali, svi hoću bit bili jer bili pobjeđuju, a mali ne želu gubit. Ali što više rastu, to više želu bit crni, jer su crni poročni, s njima se mogu poistovjetit, jer crni gubu, a život je propala bitka...!” Ponovno svi propadaju u smijeh.

“Baza svega ovoga ti je da je moreška način života”, zaključuje 49-godišnji Vojo, jedan od najstarijih aktivnih moreškanata. “Kad te vidi neko dite sa sto metara daljine kako ideš niz cestu, viče za tobom, diže ruke, oponaša pokrete moreške... uf, vidi”, pokazuje mi podlakticu “sav sam se naježi sad. To ti je to. Moreška je smisao života.”

|

The merry party continues late into the night, long after the tavern’s doors have officially closed, and I watch all the young men seated around the table and begin noticing differences in their characters.

I ask them one by one, who plays the whites, and who plays the blacks, and Toni reads my intentions. “It isn’t without reason, who’s white and who’s black!” He says.

They all take to explaining how the whites should have a stronger build; they should be taller, with poetic souls, philosophers…The blacks say about the whites that they are mommy’s boys, used to getting everything they want, thus hard bent on winning. They also admit that they really do always win, in soccer and tug-o-war. The whites strike back, saying that the blacks are feisty, snappy, rebels without a cause, losers. One of the blacks plays along; acting offended, and raises his voice.

“The bula prefers ruffians over good guys, just like all the other girls. All the whites are jealous of the blacks because the black king is alone with the bula on stage for five minutes, and the white’s never alone with her.” “But he kisses her in the end,” one of the whites laughs.

“Yeah, he kisses her cheek,” A black argues, “If we would win, we’d kiss her right. But okay, I’ll let you have it, in the play the whites win her, but after the performance, she goes with the blacks!” Laughter constantly echoes off of the tavern’s stone walls. Žitomir, the black king, brings the cheerful atmosphere to a halt saying in a serious tone “Little kids are the best example. When they’re little, they all want to be a white, because the whites win and they don’t want to lose. Then the bigger they get, the more they want to be a black, because the blacks are profane, they can identify with them, because the blacks lose, and life is a failed battle…!” They all burst into laughter once again.

“The basis of all of this is that the moreška is a way of life,” concludes forty-nine year old Vojo, one of the oldest active moreškants. “When a child some hundred meters away sees you going down the street, he yells after you, raises his arms, imitates swordfighting gestures…ah, see,” he shows me his arms, “I got goose bumps now. That’s that. Moreška is the meaning of life.”

|

Neki je drugi kasnoljetni dan na Korčuli. Starosjedioci koji su se sa svih strana hrvatske i svijeta skupili u Korčuli za svetog Todora već su se vratili svojim prebivalištima daleko od doma. Tko zna koji po redu veliki kruzer pristao je na gatove pod zidinama staroga grada. Samo galebovi koji slobodno lete plavetnilom korčulanskog neba vide da je taj brod velik gotovo kao i sâm zidinama opasan poluotok na kojem se od obale do obale već stoljećima gnijezdi Korčula. Iz pristigloga metalnoga gorostasa izlaze turisti iz cijelog svijeta i odlaze do kamene pozornice. Iz uskih ulica grada kapaju moreškanti, živi baštinici srži korčulanske kulture, njezina samog smisla. Na kamenoj pozornici počinje još jedan svevremeni boj dobra i zla. Turisti su očarani plesom boja, dinamikom bitke i njenom uvjerljivošću. Začujem jednoga kako komentira drugome da nije očekivao takav vatromet energije, da je očekivao samo još jedan folklorni nastup. Teško mogu površni posjetitelji razumjeti svu dubinu važnosti moreške za Korčulu. No lako mogu uživati u spektaklu.

Nisu ni svjesni turisti da i sami igraju dio u toj predstavi. Da se zahvaljujući njima moreška razvija i učvršćuje. Svako pleme, svako društvo, svaki narod gradi svoj identitet u odnosu prema očima izvana. Što više turista dolazi, to je više tih očiju, to je korčulanski duh snažniji. Iz kolapa u kolap bitka se razvija, raste, buja, čela se žare, iskre frcaju. I ovaj put simbolični vojnici potpuno su uronili u ples koji im, kako sami kažu, daje smisao životu. Batu kao da je to posljednja bitka.

Nakon sedmoga kolapa crni padaju, bili vijore zastave. Njihov kralj ponovno osvaja bulu. Zlo je pobijeđeno, dobro je ponovno nadvladalo. Bili kralj grli bulu i pečati pobjedu cjelovom. Turisti plješću očarani. Potom se dižu na noge i nestaju u uskim ulicama grada. No priča o moreški tad ne prestaje, nego tek počinje. Nastavlja se u prostorijama društva, gdje iscrpljene ratnike već čeka hladno pivo. Moreškanti skidaju svoja raskošna barokna odijela, ali i dalje ostaju moreškanti. Dolaze im žene i djevojke, neke stare, neke nove bule. Odlaze u svoju konobu, konobar već nosi vino i vodu, netko grabi gitaru, neki se grle, dižu ruke u zrak i počinju pjesmu. Svi se smiju. Svatko na svoj način, ali svatko s prepoznatljivim korčulanskim potpisom u jednom kutu usana.

Izvor www.rostuhar.com

|

Another day in late summer in Korčula. The natives that had come from all parts of Croatia and the world to gather in Korčula for Saint Theodore’s day have already returned to their places of residence far from home. A large cruise ship, just one among many this year, docks in the pier beneath the old town’s city walls. Only the seagulls flying carefree in the blueness above can see how this huge ship is just about as big as the enwalled peninsula itself, where the city of Korčula has been nestled from one end to the other for centuries. Tourists from all over the world pour out of this colossal metal visitor and the crowd flows towards the stone stage. Meanwhile, a trickle of moreškants – the living heritage of the heart of Korčula’s culture, Korčula’s purpose – appears from the narrow city streets. One more all-time battle of good against evil begins on the stone stage. Tourists are enchanted by the colorful dance, dynamic battle, and its persuasiveness. I hear one tourist comment to another how he had not expected such an explosion of energy, that he had expected just another folklore performance. It is difficult for superficial tourists to understand all the depth and importance of the moreška in Korčula. But it is easy for them to enjoy the spectacle.

And not all the tourists are aware that they play a part in this performance too. For thanks to them, the moreška has developed and strengthened. Each tribe, each society, each nation builds its identity according to the eyes of the outside. The more the tourists, the more the eyes watching, the stronger is Korčulan spirit. From round to round, the battle develops, heats up, foreheads shine with sweat, and sparks fly. And this time the symbolic soldiers are completely absorbed in this dance that gives them, as they say, a purpose in life. They perform as if this is their last battle.

After the seventh round, the blacks fall and the white flag waves. Their king wins the bula once more. Evil is defeated, and goodness rules once again. The white king hugs the bula and marks his victory with a kiss. Tourists applaud, enthralled. They then get up and scatter throughout the narrow city streets. But the story about the moreška does not end now; rather it is just getting started. It continues in the rooms of the society, where cool beers await the exhausted warriors. Although the moreškants take off their pompous Baroque costumes, they are still moreškants. Their wives and girlfriends come, ex-bulas and some new bulas, and they head for the tavern. The waiter already brings them wine and water, someone grabs a guitar, some sit embracing one another; others lift their arms in the air and begin singing. All of them are laughing; each in his own way, but each with a recognizable Korčulan signature to his smile.

Source www.rostuhar.com

| Translated from Croatian by Erika Katačić Kožić

|