Sponsored Ads

|

» Home

» Tourism » (E) Adventures with Jason: Croatia, Part Two

| (E) Adventures with Jason: Croatia, Part Two |

| By Nenad N. Bach |

Published

07/6/2003

|

Tourism

|

Unrated

|

|

|

|

(E) Adventures with Jason: Croatia, Part Two

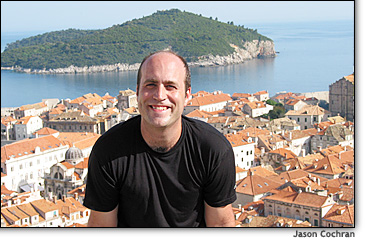

| Adventures with Jason: Croatia, Part Two | | Here I am at the Minceta Tower, the highest point on Dubrovnik's 1,000-year-old walls. Behind me, you can see the jarring mix of brown old tiles and new reddish tiles laid after the shelling 12 years ago. But Dubrovnik survives, lavish as ever. |  | | More surprises, including the legendary cities of Split and Dubrovnik, await in this Adriatic jewel By Jason Cochran

ARTHUR FROMMER'S BUDGET TRAVEL | | May 29 — I have just discovered one of the world’s great drives. I’d love to give you directions, but it’s not some three-hour Sunday excursion. It’s Croatia. The whole coast. As the crow flies, that’s about 440 miles of seashore on roads that wind around dramatic cliffs through sleepy villages, flying over crystal Mediterranean waters, surveying magnificent mountains floating in the distant sea. | IT’S EASY to forget that before the violence of the early ’90s, Croatia attracted a stunning 10 million tourists a year. Numbers are up again, but they still haven’t recovered. Which means these fabulous roads are still relatively uncluttered and 2003 is an ideal time to visit Croatia. Right now, it’s in that slim window of time in which tourist amenities are back on line but tourists themselves are straggling. (And if my dispatches from Croatia — you’ll find the first one by clicking HERE— have made you curious about going, at the bottom of this story, you’ll find a partial list of information contacts and companies that sell travel there.)

On the map, Croatia looks something like a boomerang; one prong points into Central European farmland and rings with Austro-Hungarian influences, and the other whips down the coast of the Adriatic, where Italian flavor dominates.

My plan is to drive most of the coast, from the port of Rijeka in the north to Dubrovnik at the southern end. On the map, it doesn’t look like much—essentially half the length of Italy, its neighbor about 100 miles across the Adriatic—-but the twists and turns of these vertiginous coastal roads retard progress considerably. Americans are unused to such thinly guardrailed highways, or to drops of such precipitous proportions (as well as to the bumper-hugging impatience of your average Mediterranean driver), so if you want to enjoy the view, you have to take your time. There are 1,185 offshore islands in Croatia, mostly uninhabited, and on a drive along the coast they scroll through your car window with almost magisterial grace. Under normal circumstances, I get rattled when a slowpoke truck appears at my front bumper on a long road trip, but in Croatia (where I sometimes spot rusting car wrecks clinging to the cliffs below), I’m grateful for slow traffic. Besides, it affords me chances to steal more gazes at the Adriatic. | | In Istria, in Croatia’s northwest, the weather, like the sea, is murky at this time of year. But once I pass Rijeka, the islands of Krk and Rab slide into place and Mediterranean magic takes hold. Haze and vegetation clear, leaving only ancient rock, crisp sunshine, and a sea like a basin of solid glass, with the odd sailboat skimming an imperceptible surface. | Although the Dalmatian dog may or may not have originated here, you will see a few of them trotting about, and they match nicely with the spotted white stone streets.

| For seven hours, that’s my view, as I advance into the legendary coastal region known as Dalmatia. This is the homeland of Marco Polo. Dalmatia’s island of Brac is where the white stone facing of our White House originated (yes, America; the “white” part of the white house spent more time in Croatia than in Washington). And although the Dalmatian dog may or may not have originated here, you will see a few of them trotting about, and they match nicely with the spotted white stone streets.

The next UNESCO World Heritage Site on my tour (they come fast and furious in these parts) is in the coastal town of Sibenik, about midway down the coast. The site: the Cathedral of St. James. My work takes me to many old churches. Too many, each one claiming to be a can’t-miss attraction. I know tourists who get “cathedraled-out” after just a day or two in Europe; can you imagine having a job where you had to visit them daily? Well, this is one of the few in the world that I can say is definitely worth the detour. I’m not saying that God plays favorites, but not all churches are created to be equal. This church has wicked charm. It’s worth your time, as are the steep stone streets that climb the hill behind it. | A few of the 72 faces decorating the Cathedral of St. James ("St. Jacob" in some guide books), completed in 1555. Visiting the interior is free, but be warned that you must wear long pants and enclosed shoes. Despite boasting St. James, Sibenik, a hillside town overlooking a particularly serene section of the Mediterranean, is not a touristy city.

|  St. James was begun in 1431 (its roof was smashed by shelling a decade ago, but it has been so elegantly restored that you wouldn’t know if I hadn’t told you—and that’s the case for most of Croatia’s sights). From afar, one might declare it the ideal Mediterranean church. Its cladding is nicely sunbleached and its dome (incredibly, built without mortar) is pleasingly bulbous. But up close, St. Jame’s true appeal reveals itself. A total of 71 faces, representative of 71 average Joes from the 15th century, stud the exterior in rows. Some are grinning, some frowning, some gloating, some laughing, but all are rich with a wry humor rarely seen in art of that age. It’s as if the whole building was carved as a medieval version of the opening of “The Muppet Show.” (That’s probably not what the UNESCO people had in mind when they named it to their World Heritage List, but I’m a child of the ’70s, so my reaction is either terribly sad or terribly modern. It reminds me of the time in Botswana when, after our tiny motorboat was attacked by a hippo, a fellow tourist, oblivious to how close he just came to expiring in the messiest conceivable manner, exclaimed, “That was just like the Jungle Cruise at Disney World!” But that’s another topic, and one probably left alone. Onward.)

It’s a shame that my frenized travel-writer’s schedule won’t permit me more time in Sibenik, or time in the university town of Zadar, or a hike in the limestone gorges of Paklenica National Park. Periodically, I pass a young woman or child standing at the roadside extending a fat bunch of asparagus toward my car. I wish I could buy some, but my plans are set. Finally, and regrettably after such a dazzling drive, I crest a mountain and, like something with wings, descend into the ancient city of Split.

SPLIT AND TROGIR

Split, which is about two-thirds down the coast of Croatia (roughly across the Adriatic from Ancona, Italy), is another big surprise. Get this: Much of the old city is in fact a Roman palace, built around the year 300. It is the Temple of Diocletian, my next UNESCO site, and it’s still used for homes and businesses today. While our kids pass Ross Dress For Less and Wendy’s on the way to school, Split’s kids walk past Roman temples to Jupiter and sphinx statues from ancient Egypt.

I find Split’s age impossible to grasp, even as I find myself walking through the Silver Gate into the Peristyle, surrounded by Roman columns and an ancient mausoleum, with polished ancient stone underfoot. In many parts of the world, they would put a velvet rope around the whole place. Here, there are café tables spread about, and some bored-looking teenagers abjectly exhale cigarette smoke in the vague direction of priceless antiquities. | Split’s port bustles even today with ferries heading all over the Adriatic, including Italy. There were even some American ships just in; a Coast Guard ship and a minesweeper, fresh from the Suez Canal after five months of duty. A 15-minute walk from the Temple is Bacvice, where the young and pretty people dine and dance each night, and the Hotel Park (my place), where the American ambassador sleeps during visits to Split. On my first night there, a wedding is taking place on the grounds. A male choral quintet serenades with pleading, leaning harmonies, like Bulgarian folk music; within hours, everyone is cheerfully drunk.

West of Split, very close to town, you’ll find hillside villas overlooking the sea. Even in the suburbs, people have their own vineyards, and almost everyone keeps a private garden. One of the villas was designed and built by the great sculptor Ivan Mestrovic, and today it’s a conservatory of his extraordinary work. His audacious depiction of Job is particularly moving. That costs about $2.50, but if you’re extra cheap, you can see his 1926 opus “Gregorius of Nin,” for free. It’s a tribute to a 10th-century Croatian nationalist bishop, and it stands at the northern, or Golden, gate of the Temple of Diocletian. Its left big toe has been burnished by generations of luck-seekers. | | In Split, at the steps of the Roman emperor Diocletian's former mausoleum and the Protiron, once the entry to his palace, modern-day Croatians lounge al fresco with 90-cent espressos and $1.50 beers |  As I drink a leisurely al fresco beer in the theatrically lit Temple of Diocletian, I again have that now-familiar reaction: Why aren’t there any American tourists here? The lack of Americans isn’t explained by the current mania (a deliberate word choice) for staying home. Americans have never been much for Croatia, which fell off our travel radar even before the war there.

Now, things are slowly changing. The coast is being bought up by foreigners seeking cheap summer houses, and many of the investors are American. To the consternation of locals, strong foreign currencies are sweeping in and turning once-vital communities into comatose holiday towns that stand empty for most of the year. | In Trogir, it seems like nothing has changed in 500 years. No modern buildings, no Golden Arches (what are those?), not even a phone booth or Coke machine in sight.

| A half hour north from Split by local bus ($1.50), there’s yet another UNESCO site: the island town of Trogir. It was inhabited in turn by Greeks, Romans, and Venetians, and now it survives (linked to the mainland by a blip of a bridge) as a jewel of Renaissance architecture. It really is charming. During its peak, it was an economic and artistic powerhouse, and everything retains those old cultured flourishes. Romanesque churches crowd with a tangle of medieval walls and gates, shoe-polished alleys twist beneath the watchful eyes of ancient carved angels. In Trogir, it seems like nothing has changed in 500 years. No modern buildings, no Golden Arches (what are those?), not even a phone booth or Coke machine in sight. The sensation is heightened, a local tells me, by the fact the German coach tourists have not yet arrived for the high season of July and August. My timing makes Trogir is a place of beauty and peace. | For just $2.50, buses from Split visit splendid Trogir, a richly decorated island town left largely untouched since its prosperous peak during the 15th and 16th centuries. Most sights are free, including the indulgent Cathedral of St. Lawrence, which features this fantastic Romanesque door, carved in 1240.

|  Ringed by water and sun-soaked cafes, Trogir (like much of the coast) is a place where it’s easy to spend a few hours dining outside, beneath the steeples of ancient cathedrals. Me, I have black risotto, the local specialty of Pag cheese (dry like block parmesan, but sharp), and a succession of ice cream cones loaded with gelato. Total cost: less than $10. This Mediterranean lifestyle is contagious.

But there’s no time to dally, because my itinerary takes me next to one of Croatia’s many islands. Hvar is 90 minutes by modern ferry from Split’s central port. The Temple of Diocletian recedes behind the stern and the turquoise sea carries us evenly, as the Adriatic is impossibly flat; even in open waters, the sea is placid and it irons our wake as soon as we make it. Soon, I’m making the scenic half-hour drive from Hvar’s port of Stari Grad to Hvar Town itself, on the island’s southwest coast. My car windows are rolled all the way down and the warm breezes lift off the sea to carry the constant scent of lavender, which grows on the cliffs. | Hvar Town is yet another Mediterranean dream. Within its walls are some of the finest relics on the Dalmatian coast. In this small, hillside old town, wrapped around bay so clear it induces gasps, you’ll find one of the most handsome squares on the whole coast, full of kids playing soccer around a well built in 1520. You’ll find a lovely former monastery on the sea, with a collection of Greek and Roman coins (they look freshly minted) and a heavenly garden sheltered by the same gnarled cyprus tree since the 1800s. Above the sweeping arches of the Arsenal (built late 1500s), you’ll find a 16th-century theatre ($1.50 entry) that’s said to have been the first in Europe to open itself to commoners. The entire seafront is a broad stone promenade, most of it lined with cafes and restaurants, where small boats from throughout Europe tie for the evening. Above is a well-preserved castle (try the dungeon), and the promenade leads into countless isolated coves and bays perfect for private sun worship; it rarely rains here. Tucked into otherwise anonymous lanes, you’ll find gourmet home-cooked meals, the most expensive of which will set you back only $20 a sitting. (At the “Slow Food” Restaurant, I have beefsteak stuffed with goat’s cheese and fresh capers—oh my good heavens, can you imagine?)

By now, this parade of cafes, sun, indulgent cuisine, and antiquities might be grating on you a little more than it’s grating on me. (After all, I’m the one getting the tan.) So before we reach Dubrovnik, the grand finale and one of the world’s great destinations, I’ll interject a few quibbles. One concerns hotels. Although the situation is changing as tourism increases, most have echoes of unexciting Communist-run facilities; rooms are not big, and in most of them, you can still find the switch intended to summon the chambermaids who once found employment walking each floor of the hotels. Another quibble: Although Croatia is in many ways a Western European country, it requires visitors to register with the police. Luckily, this is always done for you by the hotel’s front desk, but it does require tourists to surrender their passports upon check-in, something rarely done these days in civilized Europe. Since all the best areas of Croatia are pedestrian-only (a big plus over Italy), parking is scarce (a minus); if you rent a car, make sure it’s small, nimble, and be ready to hoof it to your hotel. Most bewildering is Croatia’s tendency to shut down to tourists during the winter. It’s not that it gets too cold; the Mediterranean is never frigid. It’s that the Germans and the Italians dry up. July and August are their peak holiday periods, so that’s when Croatia takes its hotels out of mothballs. But between mid-October and mid-April, hotel options dwindle to a slender few (although, happily, prices also drop). It doesn’t seem right. I’d gladly visit Croatia in the winter. So would most Americans I know. Then again, if more of us do, perhaps more hotels will become available then.

Croatia’s economy is tepid, however, and many older people (such as women who have lost their husbands) cruise the ferry ports and bus stations in search of tourists willing to rent accommodation in their spare spaces. If hotels are full or closed, just listen for anyone saying “Soba, soba” to you—-they’re not offering noodles but “sobe,” or a room. Expect to pay about US$20 a night if you use this entirely appropriate, common, and safe method, but make sure you know how far from town you’ll be staying before you seal the deal.

DAZZLING DUBROVNIK

And finally, the climax of my trip. After more than two weeks of never lingering longer than one or to nights, I’m relieved to come to a place where I will stay for three. My hotel in Dubrovnik is the Argentina, a plush palace that reopened only two weeks ago after over a decade of decay. You see, it was the place where journalists stayed as they covered the shelling of Dubrovnik in the winter of 1991-1992; the view of a smoldering city that you saw on your TV screens is the same view you now behold from the swimming pool, way below the hotel at the Mediterranean’s edge, over the icy surface of your hand-delivered cocktails. Only now, the smell is not of smoke but of suntan oil as Western European tourists check into one of the only fully modern super-luxury hotels in the country—-paying a bit over $100 a night for what would easily cost them $500 back home. | Seeing Dubrovnik’s fortifications shoot straight out of the azure Mediterranean is one of the most transporting experiences in world tourism.

| I can count on one hand the number of world cities that cut such as striking profile. Dubrovnik was for many centuries a fabulously wealthy city-state (like Venice, like Singapore) whose riches enabled and required it to construct massive and towering fortifications around itself. Thanks to generations of shrewd political maneuvering, it was never sacked, although a few earthquakes nearly ended the place. Today, those fantastic walls—-a mile of them—-still encircle the sumptuous red-roof jumble of the old city. Seeing Dubrovnik’s fortifications shoot straight out of the azure Mediterranean is one of the most transporting experiences in world tourism. | Sunbathers hit the beach beside one the Mediterranean's most sublime sights: Dubrovnik's eye-popping walls, begun a millennium ago, which rise majestically from the freakishly smooth Adriatic Sea. It was this perspective from which, in 1991 and 1992, the world watched the treasured old city get hammered by shells launched from above.

|  In case you weren’t aware (since Croatia is empty of Americans, I must assume our ignorance is more widespread than I’d feared), 12 years ago, Serb extremists seized a fort atop a hill above the city and lobbed some 2,000 shells into this fantastic city. Residents huddled inside the medieval forts which, incredibly, protected them from modern rockets.

Even now, historians argue whether the Serbs meant only to terrify the Croats, not destroy the city (and there’s much agreement that some on the Croatian side inflicted their own incalculable damage elsewhere), but one thing is obvious: Dubrovnik, though rebuilt, is different now. It’s a gem, of course—-just with many a new roof and the whiff of fresh paint. Its weathered, lichen-covered tiles, so famous, are now upstaged by many more luminous red tiles, glaringly fresh. Ah, well. Dubrovnik has survived cataclysms worse than this. I just wish I could have seen it before.

One of my tour guides lived through the siege. Inside the Dominican Monastery, she points to a Renaissance-era well and explains that’s where, at the time, she sent her kids to collect more water than the rations allowed. Then she points to the old man taking tickets at the monastery’s museum of priceless objects. “That man is still angry with me for it.” He waves from across the room at her.

When I tell her I live in New York City, I get her full attention. Most of the time, when I tell foreigners that I was in Manhattan on September 11, they instantly tell me where they were when they saw events unfold on television. But my guide, as a survivor of the Dubrovnik shelling, asks the single most sympathetic question that a stranger has ever asked me about it. “Did it make a terrible sound?” she asks, and that’s all she asks. (It did.)

I have walked atop the walls of Dubrovnik twice now, once clockwise and once counter-clockwise, to catch the way the sunlight plays at both angles. The entire old city is an UNESCO site, the fifth and last of my trip. I have explored every street inside the walls, plumbed both the monasteries, the old granary with its centuries-old silos, the hidden alleys full of kids playing soccer on ancient stone paths. I can’t tell you how many times I have strolled the shiny avenue of Placa. I have allowed myself to be intoxicated not just by the city itself but also by a fairly immoderate round of beers in a thatched-roof outdoor pub I found through a hidden door at the base of the fortifications. There, a few feet above the glittering Adriatic and a hundred feet below the sheer drop of the medieval walls, the pub owner (a lanky kid with a wry grin) and I sat listening to Dean Martin classics and watching the Mediterranean rub fondly against the city’s stony feet. “Standing on the Corner,” indeed! | Enjoying a leisurely evening korzo, or stroll, along the gleaming stone of Placa (a.k.a. Stradun), the main avenue in Dubrovnik's old town. Anchored by two squares, Placa is lined with outdoor cafes, bookstores, and priceless antiquities such as the Church of St. Saviour (1528), Onofrio Fountain (1438) and the Orlando column (1417).

|  On my last day here, a Costa Cruises ship pulls into the waters in front of the Argentina. It’s as massive as the old city itself, and it disgorges fleets of tenders loaded with European tourists, who obediently shuffle behind sign-toting tour guides. The day seems ruined for us independent travelers, but incredibly, the crowds suddenly dissolve after lunchtime and the ship quickly pulls anchor and departs just six hours after the day began. Those poor people, I think, as the ship glides northward. How could you see Dubrovnik, the city tour of a lifetime, in just six stumbling hours? Why would you want to?

We have already received a few e-mail letters from readers who point out, quite rightly, that there’s more to see in Croatia than the places I have just visited. But I must say that my itinerary (Zagreb, Plitvice, Opatija, Rovinj, Pula, Sibenik, Split, Trogir, Hvar Town, and Dubrobnik), crowded as it is, makes an excellent introduction to Croatia. Between those highlights, it’s easy to find your own discoveries in Hrvatska. | | Don’t let the vagaries of modern political boundaries reshuffle Croatia into the fold of Eastern European countries. It was largely built by Western Europe, and it depends on it today. It might as well be part of it. Croatia is as Italian as Venice, as Austrian as Vienna, and as much Caesar’s as Rome. | | © Copyright 2000-2003 St. Petersburg Times. All rights reserved. |

|

|

|