|

Welterweight world champion and famous inventor two Croatian compatriots

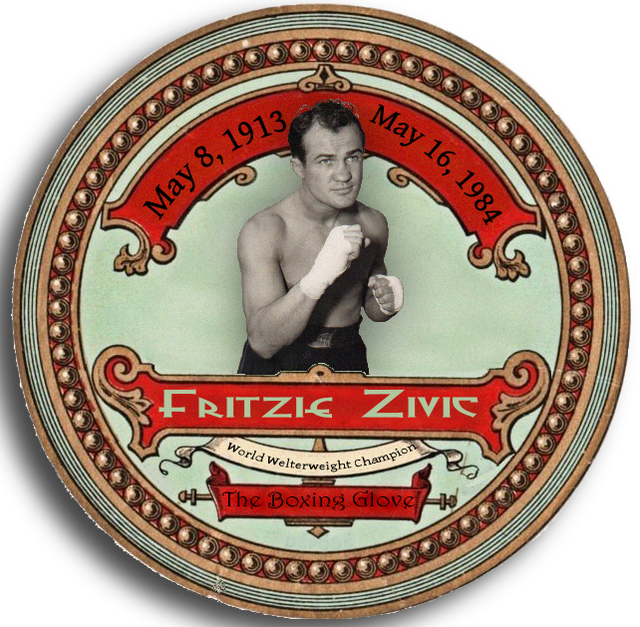

Fritzie Zivic, nicknamed the Croat Comet, welterweight world boxing champion in 1939/1940

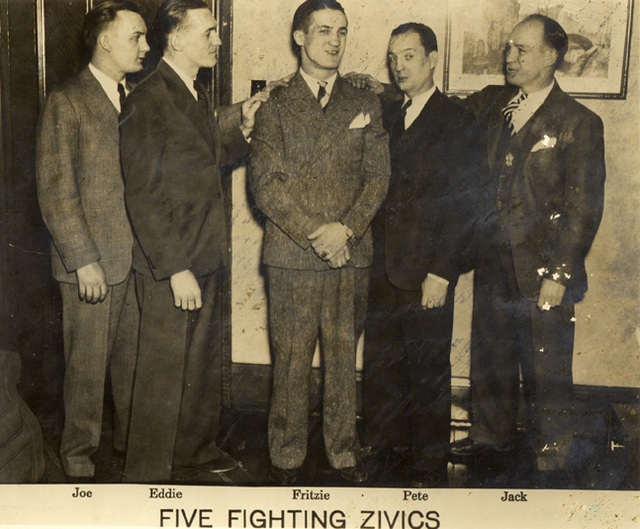

In 1941 Nikola Tesla invited to lunch with him in New York a famous Croatian-American boxer Fritzie Zivich, known under the pseudonym The Croat Comet (as well as his brothers, who were also boxers), after his successful defense of the world title in welter-weight category. Source newsinteractive.post-gazette.com. From left to right: Joe Zivic, Fritzie Zivic, Nikola Tesla, Jack Zivic, Pete Zivic and Eddie Zivic.

Summary. Fritzie Zivic never asked why. He never asked if his opponent hit hard, if his opponent deserved the shot, if the opponent would be tough. He just said “yes” and signed the contract. Perhaps this fearlessness is the reason why Zivic may have fought a better array of boxers than any fighter in history. 23,190 people filled the Madison Square Garden in New York to the rafters when when Armstrong met Zivic again on January 17, 1941. This remains the all-time highest Garden record for attendance! After this match, great inventor Nikola Tesla invited his compatriot and his four brothers to celebrate this win in his hotel. See Tesla and Zivic on the photo.

|  The Croat Comet The Croat Comet Fritzie Zivich (originally Živčić) and Nikola Tesla Fritzie Zivic was inducted to the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1993.

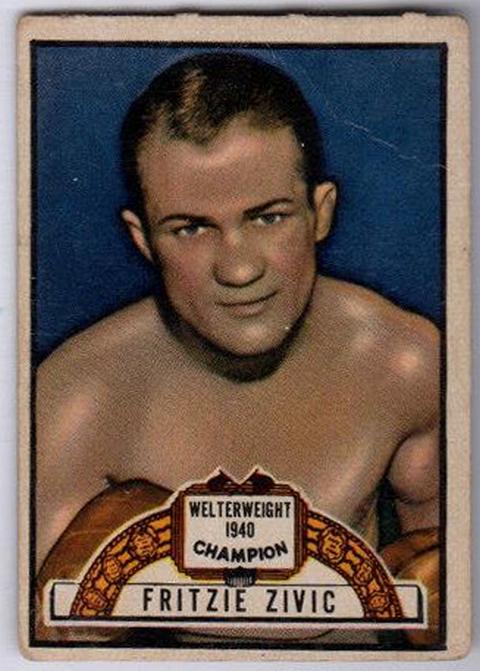

Ferdinand "Fritzie" Zivic

Welterweight Champion of the World, 4 October 1940 - 29 July 1941.

BORN: 1913, DIED: 17 May 1984.

BURIED: St. Nicholas Cemetery, Millvale.

In the early days, when immigrants surged to Lawrenceville mills and factories for jobs, nationalities respected ward boundaries, and fisticuffs were a way of life. ... Fritzie Zivic, for instance, who grew up with his four brothers in [the] 9th Ward, has said, "You either had to fight or stay in the house. We went out."

After leaving boxing in 1949, Fritzie tried promoting; managing; working in a steel mill; selling wine, whiskey and beer; bartending; and laboring on a county work crew before settling into boilermaking.

He had a body like a wire, a mind like a chess player, a quick wit and a splendid smile.

- Dennis Ruffing, "Fritzie Zivic Model One of a Kind," Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 5 February 1981, 6(South).

- John Golightly, "Boxer Fritzie Zivic Dies at 71, Former World Welterweight King," Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 18 May 1984, 8.

Source www.clpgh.org

|

Fritzie Zivic inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1993

Born: May 8, 1913, Died: May 16, 1984

Bouts: 234

Won: 159, Lost: 65

Drew: 9, ND: 1

KOs: 81

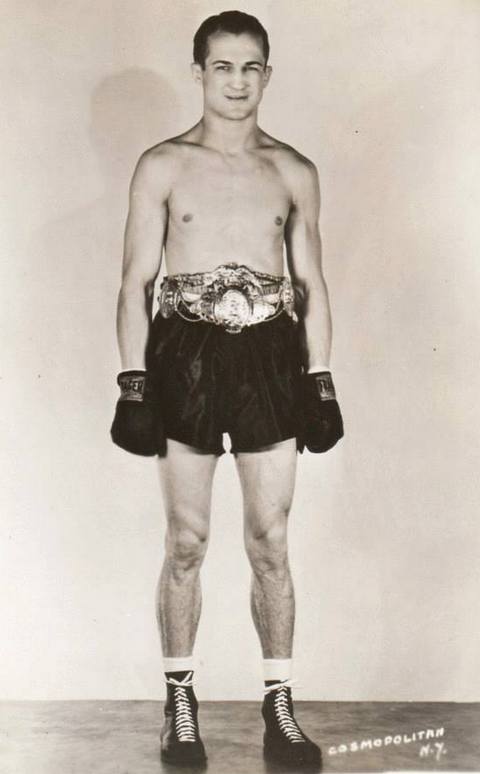

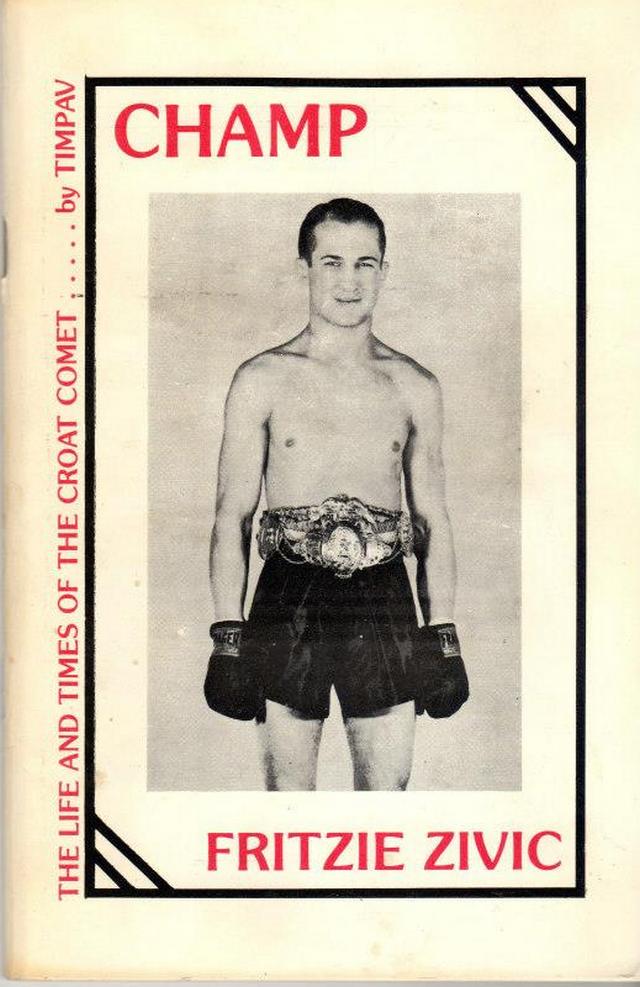

Fritzie Zivic at the start of his boxing career.

He has been inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1993

ALTHOUGH Fritzie Zivic is considered one of the dirtiest fighters in the history of boxing, he is also considered one of the best.

One of five boxing brothers from Pittsburgh, Pa., Zivic turned pro as a featherweight in 1931. By 1936, he was ranked in the top 10 in the welterweight division. He staged intra-city rivalries with other Pittsburgh fighters such as Billy Conn and Charley Burley. Zivic was notorious for using his head, elbows and thumbs as effectively as his fists. And while he was often admonished for those tactics, few could argue that Zivic also displayed tremendous determination and courage inside the ring.

In 1940, Zivic beat Sammy Angott to earn a shot at the welterweight crown. He made the most of his opportunity, upsetting the great Henry Armstrong via 15-round decision at Madison Square Garden to become the welterweight champion.

In 1941, Zivic won a rematch with Armstrong, stopping him in the 12th round. But he would lose the crown in his next defense, dropping a 15-round decision to Freddie "Red" Cochrane. Although Zivic fought for another eight years, he never challenged for a world title again.

Still, the brawling Zivic met the best fighters in the world -- ranging from lightweight to light heavyweight -- for the remainder of his ring tenure. From 1941 to 1946, he met Sugar Ray Robinson, Lew Jenkins, Jake LaMotta, Beau Jack, Bob Montgomery, Tommy Bell, Billy Arnold and Freddie Archer. Zivic continued fighting until 1949, winning his last two fights. In fact, in his second to last fight, he beat the respectable Al Reid. In all, Zivic met seven future Hall of Famers and nine world champions.

Source www.ibhof.com

|   Firtzie Zivic, welterweight champion of the world in 1940/1941 Source: Croatians in America - photo collection by Vladimir Novak

Fritzie (Ferdinand) Zivic, svjetski prvak u velter kategoriji (1940-1941), rođen je u Pittsburghu 1913. Njegov otac Josip Živić došao je u Ameriku iz Bosiljeva iz Hrvatske godine 1899. i ondje je oženio mladu Slovenku Mary Kepele. Imali su šestero djece, od toga petero sinova od kojih su četvorica bili uspješni boksači.

Fritzie je ovdje prikazan na naslovnoj stranici magazina Ring siječnja 1941.

U 230 borbi Živić je pobijedio 155 puta, od toga 80 knockoutom. Izgubio je svega u 65 borbi. Prvak svijeta postao je 4. listopada 1940., u Madison Square Gardenu u New Yorku pobjedivši "nepobjedivog" Henry Armstronga.

Povukao se 1949. u dobi od 36 godina. Godine 1972. izabran je u športsku Kuću slavnih boksača, a umro je 1984. u 71 godini. Sugar Ray Robinson je u povodu njegove smrti rekao da je o boksu naučio više tijekom deset rundi sa Živićem, nego u svim ostalim borbama zajedno.

|

Fritze Zivic, welterweight champion of the world (1940-1941) was born in Pittsburgh in 1913. His father Josip Zivic came to the United States from Bosiljevo, Croatia, in 1899, and married a Slovene girl Mary Kepele in Pittsburgh. They had six children including five boys, four of whom were successful boxers.

Fritze was featured on the cover of the Ring magazine in January 1941.

He had 230 professional fights, winning 155 fights, 80 by KO's. He lost 65 fights. He became champion of the world on October 4th 1940 in Madison Square Garden in New York, defeating "invincible" Henry Armstrong.

Fritze retired in 1949 at the age of 36. In 1972 Zivic was elected to the Boxing Hall of Fame, and in 1984 he died at the age of 71. Sugar Ray Robinson, in a tribute, said that he learned more about boxing in ten rounds with Zivic than in all his other fights put together.

|  Fritzie Zivic, pride of Pittsburgh

Fritzie Zivic vs. Henry Armstrong

It is January 17, 1941. World War II is raging in Europe, and the U.S. Selective Service Act, the former Draft Act, is only four months old. More than 23,000 fans have packed Madison Square Garden for the return bout between world welterweight champion Fritizie Zivic and the legendary Henry Armstrong. In this bout, "Perpetual Motion" all-time greatest pound for pound Armstrong tries to regain his world welterweight title from a man who knows but one rule -win.

Henry Armstrong, who had held the world featherweight, lightweight, and welterweight titles -- all at the same time -- is widely acknowledged to be the all-time greatest fighter!

Armstrong was forced to relinquish the featherweight title when he could no longer make the weight, and he lost the lightweight title back to Ambers in 1939.

Only the world welterweight title remained, and Henry successfully defended that crown 19 times before losing it to Fritzie Zivic on a 15-round decision in New York’s famed Madison Square Garden by unanimous decision on October 4, 1940. The fight was so close going into the last round that many knowledgeable boxing men thought Armstrong would win in a return.

The result, a fantastic rematch! 23,190 people filled the Garden to the rafters when when Armstrong met Zivic again on January 17, 1941. This remains the all-time highest Garden record for attendance!

The hugely popular fight was carried over radio, with Sam Taub doing the blow-by-blow and Bill Stern between rounds commentator. Blow-by-blow announcer Sam Taub started working for the old New York Morning Telegraph in 1908, working with the legendary Bat Masterson, the former western lawman turned boxing writer.

Fritzie’s elder brothers, Pete and Jack, were the first “Fighting Zivics,” representing the U.S. in 1920 Olympics at Antwerp -- Pete as a flyweight, Jack as a feather. They were the only brothers to box in the same Olympics until 1976, when Leon and Michael Spinks both won the gold.

“Perpetual Motion” Henry Armstrong scored more than his share of knockouts. In fact, his career total of 101 kayos puts him 10th on the all-time K.O. list.

Source www.amazon.com/Fritzie-Zivic-vs-Henry-Armstrong

|    Champ Fritzie Zivic Champ Fritzie Zivic, The Life and Times of the Croat Comet, biographical book written by Timpav, which is a pseudonym of Joseph M. Pavlak, an old friend of Zivic's.  The family of Fritzie Zivic in 1946.

School’s In: Fritzie Zivic Will See You Now

By Matt McGrain on May 1, 2012

“He was a great teacher,” said Billy Conn. “[Fighting Zivic] was like going to college for five years, just boxing him ten rounds…”

Fritzie Zivic never asked why. He never asked if his opponent hit hard, if his opponent deserved the shot, if the opponent would be tough. He just said “yes” and signed the contract. While LaMotta, who somehow gained the reputation for fearlessness of which Zivic was more deserving, was asked about Charley Burley, he is supposed to have muttered “Why do I need Burley when I have Zivic?” Zivic, of course, stepped out of his weight class to lose an under-celebrated series with LaMotta, and was one of the few top white contenders to ever meet the avoided Burley.

Perhaps this fearlessness is the reason why Zivic may have fought a better array of boxers than any fighter in history. In addition to the multiple contests with LaMotta and Burley, he met Kid Azteca, Bob Montgomery, Beau Jack, Henry Armstrong, Freddie Cochrane, Lew Jenkins, Izzy Jannazzo, Phil Furr, Bummy Davis, Sammy Angott, Lou Ambers and Jimmy Leto, something very close to a “who’s who” of boxing’s golden age, and he met most of them more than once. He didn’t always win, but he always gave his all and for this the people and the promoters of his hometown of Pittsburgh and beyond loved him. Other fighters? Not so much.

“He’s the dirtiest fighter I ever met,” claimed Charley Burley after his disputed points loss in their first fight. “He thumbed me over and over again.”

“When you fight for a living,” Zivic would explain years later, “if you’re smart you fight with every trick you know. If I hadn’t known nine zillion of them I never could have won the welterweight title from Henry Armstrong.”

In the modern era, fighters can come to a title without even matching a top contender. Forty fights is a career. But in the 1940s, it was unusual to see a champion with so few fights, even a young one. Like other trades, to reach the top of the heap a fighter had to become a master craftsman, the tools at his disposal needed to be of the highest quality. To this end, fighters needed to be matched often or tough or both. But there were and are some fighters who can provide a special lesson to that prospect or contender, a boxing lesson that, win or lose, crystallizes the nature of the sport for the man in the opposite corner.

Fritzie Zivic was such a fighter. Unquestionably world class in his own right, Zivic was a quick learner who took his “zillion tricks” and applied them to roughhouse boxing that tested every corner of the opponent’s make-up, technical, physical and mental. Anybody that beat him looked destined for the top, anyone that lost could still pick up more than a thing or two. Unquestionably teak-tough, a stinging if not prohibitive puncher, he could box inside or out and a tight defense and iron chin kept him to two legitimate stoppage losses in a 232 fight career. But unquestionably, Zivic’s greatest strength were his smarts, the tricks, traps and roughhouse tactics he absorbed like a sponge during his eighteen years in the ring.

In December of 1936, Zivic would teach some of these tricks to a wonder-kid tearing his way up the middleweight division, one Billy Conn. Zivic was not yet in his own absolute prime but he was twenty-three and listed as a veteran of some sixty-eight fights. Still a teenager, Conn would at least have had bulk to fall back on as a substitute for experience, weighing some seven pounds heavier on fight night at 156 and ž lbs.

Zivic started fast, attacking with both hands and Conn allowed him his way, trying to outbox and outpunch the smaller man in the pocket. This had become Billy’s habit, fighting, as he did, in a fan-friendly manner that had made him Pittsburgh’s favorite prospect. He had been in a desperately close series with resident local tough and brutal infighter “Honey Boy” Jones. According to some, he had been lucky to emerge from the third fight with a decision, his inability to adapt costing him dear in points and punches. Now Zivic fought in a style intent on taking advantage of the same flaws Jones had partially exposed, and Billy was paying for it in blood.

“Through two torrid rounds,” wrote Regis Welsh for The Pittsburgh Press, “Fritzie belted Conn to a fare-thee-well, but never quite touched the vital spot. At the end of the second…[Conn] was smeared with blood from a cut on his left cheek and a badly battered mouth.”

The press hadn’t yet been enlightened to Conn’s iron chin and it’s quite possible that Fritzie had found the “vital spot” over and again throughout the fight. As time would tell, even history’s mightiest puncher would struggle to get over on the near invulnerable Conn. However, at the beginning of the third Conn looked “tired, weary and worn out” and “in the fourth and fifth, Zivic, in a rushing charge, bore Conn to neutral ropes and belted him about the head and body until it seemed that the anticipated kayo was inevitable.”

It needs to be said though, that in spite of his fighting the wrong fight, Conn was doing his own good work, mainly to the body. Some reports credit Conn with turning the fight with a body punch as early as the third, but whilst the supposed fight of two halves (Zivic winning the first five, Conn coming back in the second half of the fight) did not occur, it’s unlikely that Conn’s hooks had the supposed affect this early. Only two judges scored the third for Conn, and all three gave Zivic the fourth. Conn wouldn’t win a round on all three judges’ scorecards until the sixth.

It was in the sixth round that Conn cracked, and went outside. In the seventh and eighth Conn “boxed beautifully…he danced, feinted, pranced and punched.” Zivic, now out of his element as a bullying counterpuncher and destructive infighter struggled to get past Billy’s “piston-like” jab. Conn had been trained for this by defensive specialist Johnny Ray from the very beginning, but he had been unable to make the transition in the ring until Fritzie had forced it. As one would expect, Zivic now changed tactics too, gunning almost exclusively for the body, only hunting Conn with power punches, bringing him the eighth round on one card. In the tenth, they went at it toe-to-toe again. “The boys used everything but knives,” wrote the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. “A wild-eyed crowd looked on.” The final round was shared on the three official cards resulting in a split decision win for Conn (6-3-1, 5-4-1, 4-5-1).

“From a mile in the rear to a nose in front takes heart in a man or a horse,” wrote Welsh in The Press. “Particularly in a novice of Conn’s immature ring experience against a seasoned veteran of Zivic’s type.”

Zivic’s type indeed! Fritzie was hell on wheels for a young fighter, one that hadn’t seen a top class cutie, never mind a back-alley wizard. But Conn knew what that fight had been worth, and he knew he was the better for it.

“He was a great teacher. [Fighting Zivic] was like going to college for five years, just boxing him ten rounds…I learned a lot in that fight. He’s a tough fighter, but I believe I’m just as tough.”

It’s a double lesson for a relative novice like Conn. First, he remembers every foul, every slither out of sight of the referee, every feint that cost him a round, every dig inside on the break. But it also teaches him that he can take it, that he can get in there with world-class fighters who know more than him and beat them. The first lesson is priceless, but the second can be the key to a career. Over the next twelve months the young Conn, who had struggled so desperately with Honey Boy Jones only three months earlier, would defeat great champions and ring legends such as Teddy Yarosz, Young Corbett III and Vince Dundee before adding Fred Apostoli and Solly Krieger and annexing the world’s light heavyweight title in 1939.

In 1941 he would be matched with the great Joe Louis. It would be unfair to Conn’s great trainer Ray, and to Conn himself, to lay too much credit for Conn’s legendary performance at Zivic’s door, but Conn’s tactics against Louis—mixing careful, punch-picking infighting with beautiful movement and judge of distance on the outside—were basically a more perfect version of the tactics he used in rounds six, seven, eight and nine against Zivic.

The Zivic matchbook.

As for the teacher, he was naturally disappointed and was keen on a rematch, but fate was to intervene. Zivic would contract pneumonia the following summer whilst training for a match with Vince Dundee. Chet Smith, then editor of The Pittsburgh Press:

“There didn’t seem to be a chance for him…so we collected all we knew about him, wrote it into a story and sent it to the composing room…There were two weeks when it was touch and go with Fritzie, and the hospital folk refused to give out a single cheerful bulletin. We knew of course when he finally came out of the hospital that his boxing days were ended.”

I guess Zivic would have snorted at that. However they build them out in Zivic’s ancestral Croatia, they build them tough because Zivic was not only far from ended as a boxer, he would go on to get better. There were more lessons to give out. The greatest fighter that would ever draw breath, he needed a lesson.

“I learned more in these two fights with Zivic than in all my other fights put together!”

So said Ray Robinson after pulling of the extraordinary feat of stopping Zivic in January of 1942. But this was the second time Zivic, a rarity in that he never discriminated against opposition on the grounds of color or quality, had met Robinson. The first had occurred when Zivic had already slipped past his absolute prime, in October of 1941.

Fritzie Zivic signed his photo in 1944

“It might have been a draw. It was close,” wrote The Telegraph Herald, but Zivic, the heavier man for a change, looked unsurprised at the unanimous decision against him. In the middle rounds he had, to a degree, had his way with Robinson but Sugar’s explosive domination of the ninth had left him struggling and at no time had he solved the Robinson jab. He knew he was beaten. “[Robinson] took a unanimous decision with such a convincing demonstration of speed and power,” wrote the Berkeley Daily Gazette, “that he will be favored to win the title.”

Robinson was learning from Zivic the same thing Conn had, that he could master a man at the next level, a veteran, a bigger one at that. But he learned more specific and unpleasant lessons in this fight, too.

“He was about the smartest I ever fought,” Robinson would later say in conversation with writer WC Heinz. “…he showed me how you can make a man butt open his own eye…he’d slip my lead, then he’d put his hand behind my neck and he’d bring my eye down on his head. Fritzie was smart.”

He also taught Ray that he could coast a little in those middle rounds, that at the highest level he didn’t need to put forth every ounce in every moment, that he could let the occasional round go as long as he was paying attention. The same pattern that Sugar used in his first fight with Zivic he would use in his sixth fight with LaMotta, for the middleweight title, contesting the early rounds, easing off in the middle, and finishing so strongly as to stop the unstoppable, lifting the title on a late TKO. He sharpened that tool for the first time against Zivic.

By now Zivic was almost past the stage of teaching fighters of Robinson’s caliber lessons, but he had one more to give in their second fight just three months later.

Firstly, Robinson showed the importance of a lesson learned, nullifying Zivic’s darker arts, like Conn he was a better fighter for his 10 rounds in the ring with Fritzie. He worked hard to the body in clinches he couldn’t contest with craft or strength (something else he would repeat against LaMotta in their title meeting) and he was careful to break clinches at any cost when Zivic looked to utilize those lethal butts. When his opponent tried holding and hitting on the referee‘s blindside, instead of trading he would dance away. Robinson had learned that the man who owned the real estate would win the negotiation and Zivic was being outclassed as a result. Of the first six rounds he banked perhaps the first. In the seventh though, Robinson momentarily forgot himself and Fritzie delivered his last lesson. As Robinson came in Zivic stepped back and cracked Robinson with a left hook. “It really hurt. I was coming in and it met me on the chin!” Robinson would say afterwards that it was the hardest punch he had ever been hit with, according to The Afro American.

In the middle of the ninth, Robinson dropped Zivic with a perfect mirror image of the punch he had been shown in the seventh, using the right hand to ditch the heavier man as he was on the way in. Up at nine, Zivic never recovered, and although he was likely stopped prematurely in the tenth, he had nothing left to teach, at least not to Sugar. At 28-0, Ray, like Billy before him, saw his 20 rounds with Zivic as nothing less than finishing school for one of the most storied careers in boxing. They are only two of the dozens of fighters that Fritzie took to school, but perhaps they are the gifts he helped in giving that we can be most grateful for—though fans of Charley Burley might be given to disagreement.

For the purposes of this article we’ve taken a look at three Zivic losses. I hoped, by looking at his fights with Billy Conn and Sugar Ray, we might see the benefit of letting a top prospect meet a dangerous genius-thug like Fritzie, the self-proclaimed “second dirtiest fighter in history.” But Zivic did lose those fights. Let it not be forgotten then that between losing to Conn and Robinson, Zivic lifted the world’s welterweight title, destroying with a mixture of aggression, uppercuts and that dirty bag of tricks for which he remains famous, one Henry Armstrong. Zivic finished Armstrong as title material, beating him for the championship of the world not once but twice.

A 4-1 underdog, Zivic had been magnanimous about his own chances going in to their opener.

“If I lose it won’t be the first fight I lost, and if I win it, it won’t be the first fight I won.”

But Zivic had learned his own brutal lessons across the years and would be merciless in bringing them to bear. Also across the years, between his title win and these more enlightened times, Zivic’s achievement in beating Armstrong has been undermined. Armstrong was old. He was past his best. Zivic had to get dirty to do it. Well all of that may be true, but it needs to be remembered that Armstrong had gone undefeated in thirteen bouts prior to meeting Zivic and that all of these fights were in defense of his welterweight crown, outside of one, his celebrated tilt at the world middleweight title. It needs to be remembered that in the previous three months, Armstrong had knocked out world-class contenders Phil Furr and Lew Jenkins. It needs to be remembered that Armstrong had his own bag of tricks, and that referee Arthur Donovan’s famous refrain, “if you guys wanna fight like that it‘s okay with me” was prompted by an Armstrong foul and not a Zivic one.

Most of all it needs to be remembered that Zivic never asked why, he just signed the contract. Whichever way you want to look at it, they just don’t make ‘em like that anymore.

Source http://www.boxing.com/fritzie_zivic_will_see_you_now.html

|  Fritzie Zivic in 1966

Fritzie Zivic in 1977 Young Eddie and Fritzie Zivic Young brothers Eddie and Fritzie Zivic

Formated for CROWN by Darko Žubrinić

Distributed by www.Croatia.org . This message is intended for Croatian Associations/Institutions and their Friends in Croatia and in the World. The opinions/articles expressed on this list do not reflect personal opinions of the moderator. If the reader of this message is not the intended recipient, please delete or destroy all copies of this communication and please, let us know! |