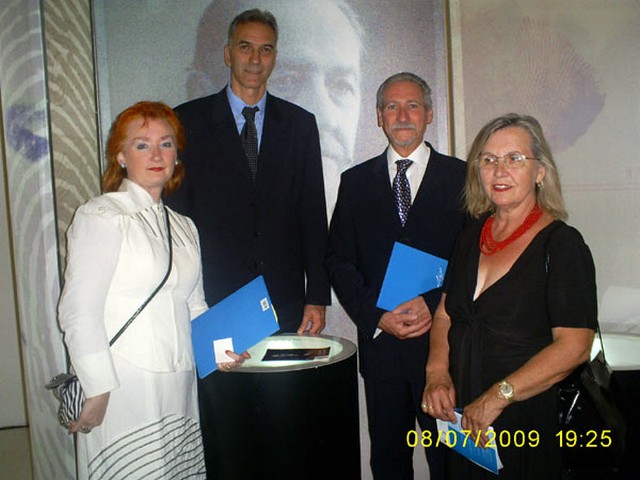

| An important exhibition dedicated to Ivan Juan Vučetić, founder of scientific dactiloscopy - identification by fingerprints, has been organized in Milan from July 8-20 2009, in the representative building of Palazzo Triennale It was conceived by Ljerka Galic from the Croatian Hertage Foundation in Zagreb, who opened the exhibition in the presence of Consul General of Argentina, Consul General of Croatia, representatives of Italian State Police and other guests. |

| Izložba Ivan Vučetić u Milanu Od 8. do 20. srpnja 2009. na prvom katu najreprezentativnijeg izložbenog prostora grada, Palazzo Triennale (izgrađenoj namjenski 1933. za potrebe izlaganja suvremenih dizajnerskih dostignuća) kulturnoj javnosti grada Milana prikazana je multimedijalna izložba "Ivan Vučetić", svehrvatski projekt Hrvatske matice iseljenika, kojim je tijekom prošle godine obilježena 150. godišnjica rođenja hrvatskog iseljenika u Argentinu, izumitelja najmjerodavnije i najjednostavnije klasifikacijske metode po otisku prsta.  Kako je Grad Zagreb s gradom Milanom potpisao akt o suradnji na mnogim poljima, tako i kulturnom, ukazala se prilika da se inozemnoj publici predstavi baš ovom izložbom, te ostvari suradnja s Talijanskom državnom policijom - kvesturom Milano, koja je svoje djelovanje također predstavila u okviru izložbe HMI. U organizaciji Hrvatske zajednice u Italiji - Milano i predsjednice Snježane Hefti, te Damira Murkovića, predsjednika Hrvatske zajednice u Trstu, na otvorenju su se nazočnima obratili predstavnici svih partnera uključenih u projekt: Jasna Matković (MUP RH), dr. Menna (Talijanska državna policija), dr. Agnesi (u ime domaćina izložbenog prostora Triennale), te Andro Knego, generalni konzul RH i Gustavo Moreno, generalni konzul Republike Argentine, budući je Ivan Vučetić umro i pokopan kao državljanin Argentine 1925. godine. U ime HMI izložbu je otvorila začetnica i realizatorica Projekta Vučetić Ljerka Galic. Poznato je da je Ivan/Juan Vučetić/Vucetich vrlo cijenjen u policijskim krugovima diljem cijelog svijeta, te su stoga izložbu posjetila i gospoda iz Museo Lombroso iz Torina, s kojim se on i dopisivao. Ljerka Galic, www.matis.hr |

Building of Palazo Trienalle in Milan where the exhibtion dedicated to Ivan Vučetić was organized in July 2009.

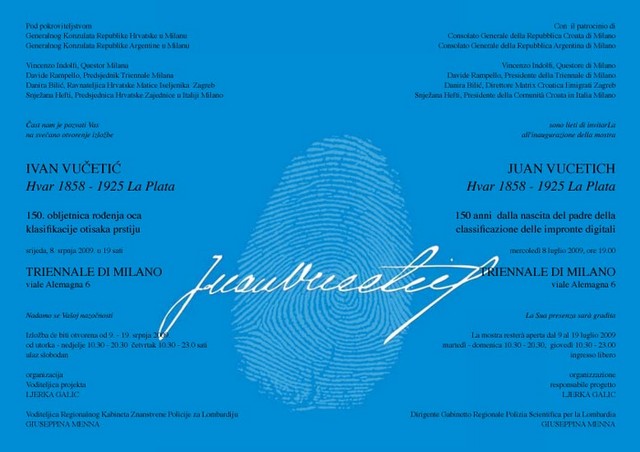

The announcement of the exhibition in Milan.

Snježana Hefti, president of Croatian Community in Italy, addressing to the audience during the opening ceremony of the exhibition.

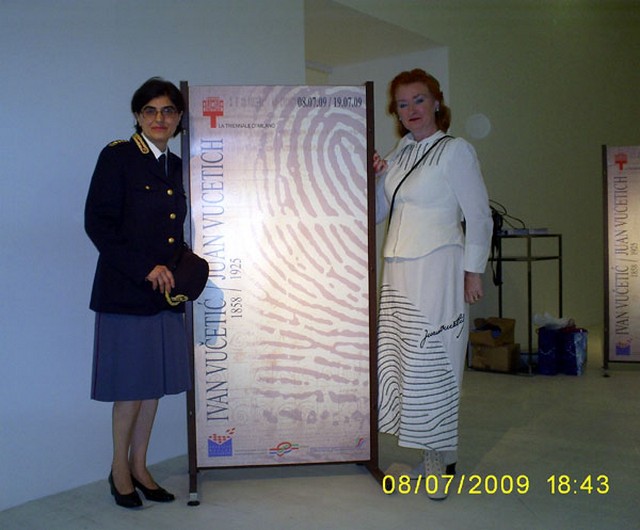

Dr. Agnesi in the name of Italian hosts and Ljerka Galic from Croatian Heritage Foudnation in Zagreb. Note that her dress is inspired by Ivan Vučetić and fingerprints.

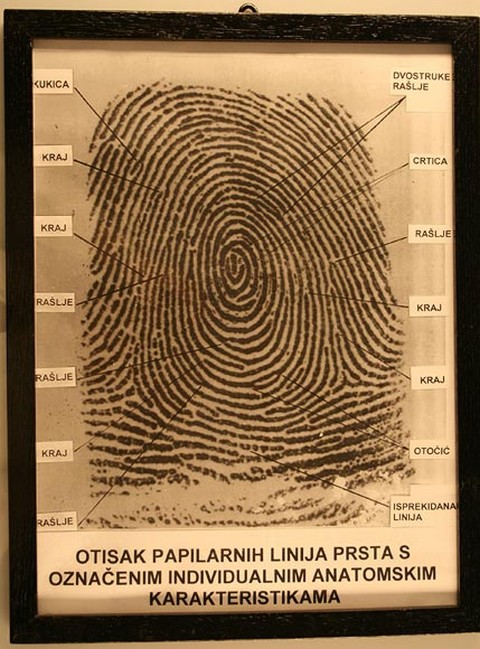

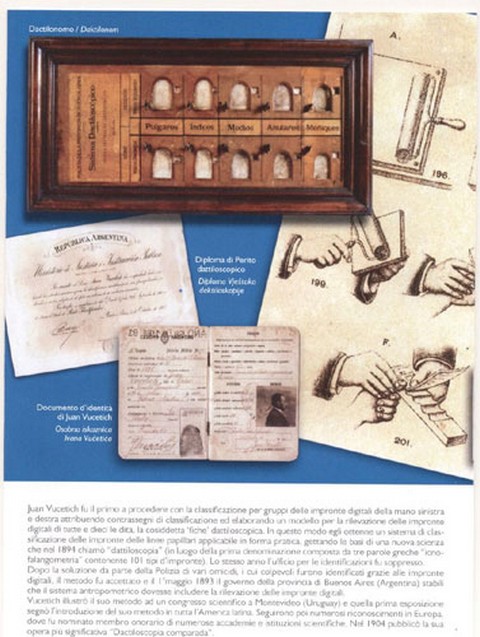

Exhibits in Palazo Trienalle in Milan related to life and work of Ivan Juan Vučetić.

Ivan Vučetić in his hometown Hvar on the island of Hvar in Croatia at the beginning of 20th century.

| Argentina pioneering forensic science in the 1800s By Eric Stener Carlson Argentina has made recent moves to overcome its long history of human rights abuses. The once-feared ESMA naval engineering academy now houses a human rights centre. Cases against kidnapping of children have been reopened, and Argentina is a member of the newly-formed Human Rights Council of the United Nations. But long before the Dirty War, Argentina was a world leader in the fight against torture. Towards the end of the 19th century, one man was synonymous with a movement that favoured scientific investigation over torture, of rights over brutality. That man was the Argentine police officer and scientist, Juan Vucetich. Juan Vucetich, born in present-day Croatia in 1858 (then part of the Habsburg empire), emigrated to Buenos Aires in 1884. The son of barrel-makers, Vucetich was a prodigy in music, languages and mathematics. In 1888, Vucetich moved to the brand-new city of La Plata, where he joined the Office of Accountancy and Majority of the Buenos Aires provincial police. It was there he immersed himself in the field of anthropometry, the study of bodily measurements to identify criminals. However, Vucetich soon became convinced that anthropometry was deeply flawed, resulting in mistaken identities and innocent people being imprisoned for crimes they did not commit. He then taught himself the budding science of fingerprinting, with amazing results. Vucetich developed a revolutionary method of classifying fingerprints into four different types. This method forms the basis of the modern National Identity Documents still in use in Argentina today. But the biggest test of Vucetich's system of fingerprinting came in 1892, when it was used to resolve a murder, a first in the history of criminology. On June 29, 1892, in the city of Necochea, Francisca Rojas killed her two children, Ponciano Caraballo, six years old, and Felisa Caraballo, four years old. Rojas barricaded herself in her house and slit her children's throats. Then Rojas stabbed herself superficially, trying to make it look like she was the victim of the same attack. Rojas then accused a neighbour named Ramón Velázquez of having committed the murders. She blamed Velázquez for revealing an infidelity to her husband, with the result that she was about to lose custody of the children. In parallel, Buenos Aires provincial police chief Guillermo J. Nuńes sent a police officer from La Plata to further investigate the crime. His name was Eduardo M. Álvarez, a colleague of Vucetich and well-versed in his fingerprinting techniques. Álvarez's mandate was "to obtain the traces of the fingerprints left by the criminal and [to bring back] the proof." Upon arriving to Necochea, Álvarez made an awful discovery. As he wrote in his report to Nuńes in July, 1892: "I have been able to observe that the Seńor Comisario from Necochea, completely forgetting the prohibitions that our regulations establish, and all good sense, has committed the serious error of applying moral punishments to the author of the crime, to obtain her declaration." By "moral punishments," Álvarez meant the police had made Rojas attend una capilla ardiente, a vigil next to the bodies of the dead children. The police had also forced Velázquez to view the corpses, in the hopes that the gruesome scene would force a confession. As both Velázquez and Rojas maintained their innocence, the Necochea police continued with "diverse questioning." It is likely the police tortured Velázquez, as beatings and the "submarine" -nearly drowning suspects until they confessed - were common police interrogation techniques in 19th century Argentina. Whatever abuse the police used, Álvarez described it in a letter to Vucetich, as "unacceptable methods." Finding the police methods unacceptable and the confession in doubt, Álvarez returned to the scene of the crime and employed Vucetich's methods. He found a bloody fingerprint on the door where the double murder was committed. He cut the piece from the door, had the impression analyzed and proved it came from the mother of the murdered children. With this evidence, Álvarez ordered Velázquez's release, and Rojas was tried and convicted as the sole author of the crime. Much has been made of the scientific aspects of the Rojas case. Indeed, Vucetich's methods created a shockwave throughout the field of criminology. In a series of scientific congresses, Vucetich was lauded for his discoveries, and his system was quickly adopted throughout the world, from Bolivia to Norway, from China to Romania. However, the moral implications of the Rojas case outweigh the scientific ones. As Álvarez himself observed, there were so many clues pointing to Rojas' guilt that her fingerprints were almost superfluous. Rojas had locked herself inside with her children, had killed them with her own knife and had hidden the murder weapon in the roof of her house. But the Necochea police still used torture because the concept of suspects' rights was almost non-existent. When Police Chief Nuńes ordered Álvarez to search for fingerprints, and when Álvarez recoiled at his discovery of the capilla ardiente, it was Vucetich's philosophy at work more than his science. In an unpublished manuscript by Vucetich, begun in 1920 and entitled Historia Sintética de la Identificación, Vucetich comes across as a man deeply preoccupied with basic human rights. He writes of the history of police abuse, including branding of prisoners for future identification. One quote in Vucetich's manuscript, from Yves Guyot, a 19th century French criminologist, exemplifies his philosophy: "The police should make use of the discoveries of science. It is not through their brutality but through their intellectual superiority that they can guarantee security." Therefore, while it is important to overcome Argentina's history of human rights abuses, it is also important to recall the country's history as a world leader against torture. Vucetich's legacy is that science should serve humanity and that a system of justice should be measured by how it protects the rights of all. It was this moral drive behind the science that set Vucetich's methods apart from those of many of his contemporaries, and it is a lesson that should be rediscovered today. *Note: Dr. Carlson is author of I Remember Julia: Voices of the Disappeared and The Pear Tree: Is Torture Ever Justified?, and he is an Honorary Member of the Fundación Juan Vucetich. This article draws from the author's Spanish-language article, La Verdadera Herencia del Caso Rojas, which appeared in Todo es Historia No. 484 (September 2008), to commemorate the 150th anniversary of Vucetich's birth. Source www.buenosairesherald.com |

Formated for CROWN by prof.dr. Darko Žubrinić

Distributed by www.Croatia.org . This message is intended for Croatian Associations/Institutions and their Friends in Croatia and in the World. The opinions/articles expressed on this list do not reflect personal opinions of the moderator. If the reader of this message is not the intended recipient, please delete or destroy all copies of this communication and please, let us know!