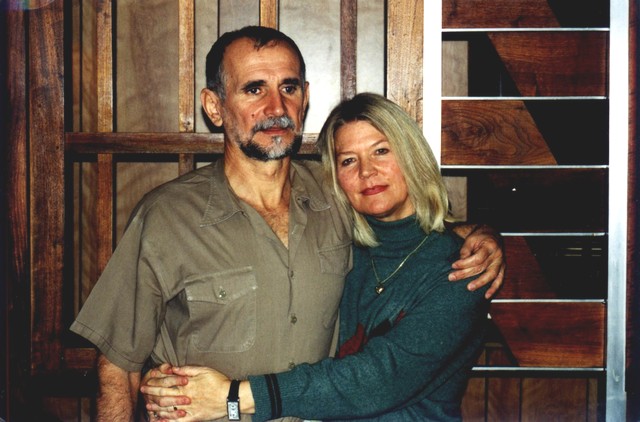

| | Julienne Eden Bušić's speech at the book promotion, "Your Blood and Mine", held in an overcrowded hall of the Mimara Palace in Zagreb, May 21, 2009, in the presence of her husband Zvonko, both on the photo from 1970s. They met each other again in 2008 after 32 years of separation. |

| Promocija knjige Julienne Eden Bušić "Tvoja krv i moja" 21. svibnja 2009. u palači "Mimara" u Zagrebu U zatvoru sam boravila s mnogo živopisnih likova, među kojima su bile i dvije najluđe djevojke iz skupine koja je njegovala kult Charlesa Mansona - Lynette Fromme i Sandra Good. Nosile su prsluke ispletene od Charlijeve kose i činile lude stvari poput zakopavanja kosilice kako ih ujutro kosilica ne bi budila pod prozorom ćelije! Lynette me pokušala ubiti čekićem za izvlačenje čavala jer joj nisam željela biti prijateljicom, ali na moju sreću u blizini su se zatekli čuvari pa sam prošla samo s potresom mozga, gomilom šavova i dobrom pričom koju mogu ispričati. Dakle, očito nisam obožavateljica obitelji Manson. No bez obzira na to, zanimljiv je bio odgovor što ga je Manson prije mnogo godina dao novinaru koji ga je upitao je li lud: "Čovječe, ja sam bio lud kad je to nešto značilo. Danas su svi ludi." Njegov je odgovor još točniji danas, kada svi nisu ludi, nego su svi teroristi: ekološki aktivisti, protivnici pobačaja, pa čak i računalni hakeri..., sudeći po mjerilima američkog Ministarstva unutarnjih poslova. Što se dogodilo s "dobrim starim vremenima" kad su postojali pravi teroristi? Crvene brigade, na primjer, ili Frakcija Crvene armije. Oni su uistinu s namjerom ubijali ljude, uvijek iznova, mnoštvo njih. Ili Nelson Mandela koji je otvoreno zagovarao nasilje i upravljao organizacijom odgovornom za stotine smrti civila i tolika bombardiranja. Ne zaboravimo ni državni terorizam, od Gulaga do Gologa otoka. Mnogi od vas, koji ste večeras u publici, bili ste žrtvama takvoga terorizma. U novije vrijeme imamo Guantanamo koji je sad, na svu sreću, u postupku zatvaranja. I premda odajem priznanje studentima štrajkašima u Hrvatskoj - koji bi, po definiciji nekih vlada, također bili teroristi - i koji su pokazali mnogo duha i duše, znam da im za to nije trebalo mnogo hrabrosti. U bivšoj Jugoslaviji svi bi oni završili u zatvoru, neki bi bili mučeni, a neki bi možda i podlegli. Takvo je stanje bilo jedan od razloga zašto smo 1976. oteli zrakoplov: oteli smo ga kako bismo privukli pozornost svijeta na zločine u Jugoslaviji, kako bismo primorali zapadni, demokratski tisak, koji nije mario, da objavi naš letak s popisom kršenja ljudskih prava, utamničenja, umorstava. No za razliku od Frakcije Crvene armije, Crvenih brigada, Nelsona Mandele i drugih, mislim da bi nas trebalo zvati lažnim teroristima, jer nismo zagovarali nasilje, pokušavši ga izbjeći, i nipošto nismo namjeravali ozlijediti druge. I jedina je smrt u našemu slučaju bila slučajna, a ne namjerna. Zbog nje ćemo gorko žaliti do kraja života. Neki se od vas već sada možda pitaju jesu li u pogrešnoj prostoriji. Zar ovo ne bi trebalo biti predstavljanje knjige? Zar ne bismo trebali govoriti o epistolarnom romanu ili o memoarskoj prozi, umjesto o neugodnim temama poput terorizma? Da, trebali bismo, u racionalnome svijetu, ali osjećam kako najprije moram opravdati svoje, naše (mene i Zvonka) razloge i pravo da budemo ovdje. I to zbog posvudašnjeg "gakanja" pojedinih hrvatskih medijskih komentatora, samoprozvanih moralnih arbitara svijeta, tobožnjih aktivista za zaštitu ljudskih prava, zajedljivih književnica u dragovoljnom izgnanstvu, vječnih policajaca, kako ih ja nazivam, koji vjeruju kako su oni koje smatraju teroristima proigrali svoje pravo da se uklope u svijet i da konačno slobodni - robijanjem plativši svoj izbor, žaleći zbog nevine žrtve otmice i odležavši kaznu - idu za osobnim stremljenjima, da se pojavljuju u javnosti, da pišu knjige... Njima se, dežurnim policajcima, ispričavam što smo ovdje, u svom našem sjaju! Ali, smije li nas se doista i dalje kriviti? Naposljetku, ohrabrila nas je činjenica da drugi, pravi teroristi redovito pokazuju svoje lice nimalo se, naizgled, ne stideći. Nije li nepokajnik Mandela nedavno u Londonu proslavio devedeseti rođendan, u društvu devedeset tisuća gostiju, među kojima je bio i britanski premijer? A prošloga je svibnja Karl Heinz Dellwo, bivši član Frakcije Crvene Armije - terorist ili revolucionar, birajte što vam je draže - u Zagrebu iznio svoja razmišljanja u hrvatskim medijima, ne baš na naročito dubokouman način: "Bilo je i nasilja", reče, "no iza toga je ipak stajao koncept". O četvero poginulih ništa nije rekao, važno da je postojao koncept. Za ubijanje. Nije spomenuo kako se osjećao zbog toga, što je naučio u zatvoru, ni čemu bi mogao druge podučiti. U brojnim je medijskim nastupima samo ponovio prazne klišeje svoga vremena. Dellwo je pušten nakon što je odslužio samo dvadeset godina, umjesto dvije doživotne zatvorske kazne na koje je bio osuđen, a zbog smrti četvero ljudi u Stockholmu. S druge strane, samoprozvani moralni arbitri kažu kako bi mediji morali šutjeti o Zvonkovu povratku kući nakon trideset i dvije duge godine, i o našemu slučaju općenito. Premda mi nismo suglasni udovoljiti im svojim nestankom, i dalje drže kako bi nas trebalo izbrisati, barem iz medijskog prostora, kao što su u nekadašnjim diktaturama s fotografija brisani političari koji bi pali u nemilost. Razmislimo nakratko o temeljnim činjenicama. Mladi hrvatski idealist odlučuje se na drastično otimanje zrakoplova kako bi pozornost svijeta svrnuo na strašna kršenja ljudskih prava, utamničenja i umorstva svojih sunarodnjaka. Zbog svojih ideala više od pola života provodi u zatvoru i time u cijelosti plaća dug društvu. Njegova supruga Amerikanka, koja s Hrvatskom nema drugih spona osim ljubavi, napušta svoj udoban i, priznajem, razmažen život kako bi poduprla supruga i provodi trinaest godina u zatvoru, a nakon toga vjerno čeka da on odsluži ukupno trideset i dvije strašne godine. Možda sam ja malo pristrana, ali meni to zvuči kao priča koju bi ljudi ipak željeli čuti i čitati je i, ako je to dvoje ljudi zavirilo duboko u svoje duše, možda bi drugi iz te priče htjeli naučiti važne lekcije. Kakav je osjećaj nakon dvadeset i više godina prvi put vidjeti zvijezde i mjesec, kao Zvonko? Kako čovjek uspijeva emocionalno preživjeti veoma stvarnu mogućnost da će njegov ljubljeni ili ljubljena umrijeti u zatvoru, što sam ja uspjela? Kako čovjek bez pritužbe nosi i tuđu i vlastitu krivnju, kao što ju je Zvonko nosio nakon 11. rujna 2001.? Ljubav, krivnja, strast, žrtva, ponos, radost, suosjećanje... - gdje čovjek pronalazi snagu otrpjeti duboku patnju, koje se egzistencijalne lekcije mogu naučiti, kako drugi mogu proširiti i obogatiti svoje živote kroz duboku bol i je li žrtva vrijedila truda? Čak i da ovo nije naša priča, mene bi zanimala. Željela bih čuti takve ljude, čitati o njihovim iskustvima. Nije li to normalna reakcija? Jer ono što oni imaju reći, ako uistinu znaju dobro reći, služi dvjema svrhama: kao književnost spoznaje i književnost moći, da poduči i, što je važnije, da gane, kao što je postulirao Thomas de Quincey u svome glasovitom eseju. Spoznaja nam daje obavijesti, saznajemo nešto konkretno što prije nismo znali, a u našemu je slučaju presudno znanje o onomu što se doista zbilo, a ne izvrtanja i laži. Književnost moći pak nastoji nas ganuti, napregnuti i proširiti našu latentnu sposobnost suosjećanja s beskonačnim, gdje je svaki otkucaj i svaki zaseban prinos korak uvis... Zato sam sretna kada čujem da smo mnoge ganuli, pa čak i nadahnuli svojim riječima. Zamislite, na trenutak, snagu i moć koje bismo bili lišeni da su ljudi koji su počinili nezakonita djela bili prognani, izbjegavani, izolirani ili spriječeni govoriti i pisati o svojim iskustvima: Dostojevski, Jean Genet, Vaclav Havel, Ezra Pound, Aleksandar Solženjicin, Oscar Wilde, pa čak i Nelson Mandela. Svijet bi bio turobno mjesto bez Wildeovih riječi iz djela De Profundis: "Mnogi ljudi po otpustu iz zatvora nose zatvor sa sobom i skrivaju ga kao tajnu sramotu u srcima, i najzad, kao nesretni otrovani, zavuku se u nekakvu rupu i umru. Grozno je što to moraju učiniti i pogrešno, silno pogrešno od društva da ih na to primorava. Društvo si uzima pravo užasno kazniti pojedinca, bolujući ujedno od krajnjega poroka, površnosti, i ne shvaća što je učinilo. Kad čovjek otrpi kaznu, društvo ga prepušta samome sebi; drugim riječima, napušta ga upravo u trenutku kad započinje najveća obveza društva prema tome čovjeku. Silno se stidi vlastitih djela i izbjegava one koje je kaznilo, kao što ljudi izbjegavaju vjerovnika kojemu ne mogu platiti dug, ili nekoga kome su nanijeli nepopravljivu, neizlječivu krivdu. Sa svoje strane mogu tvrditi da, ako sam ja shvatio što sam pretrpio, i društvo bi trebalo shvatiti što mi je nanijelo; ni sa jedne ni sa druge strane ne bi smjelo biti nimalo gorčine ni mržnje." I još jedna Wildeova misao: "Zatvorenici znaju samo za jedno godišnje doba - doba Žalosti. Kao da su nam oduzeli i Sunce i Mjesec. Vani je možda plav i zlatan dan, ali kroz debelo mutno staklo prozorčića sa željeznim rešetkama, ispod kojeg sjedi zatvorenik, provlači se sivo i škrto svjetlo. U njegovoj ćeliji uvijek je sumrak, kao što je u njegovu srcu uvijek ponoć." Međutim, umjesto riječi prosvjetljenja, introspekcije, prizorā i slikā koje će uzvisiti ljudsku dušu, samoprozvani moralni arbitri uporno se podsmjehuju ljubavi, ne obaziru se na svece i grade spomenike dekadenciji. Zar ne shvaćaju da je uzaludno ponavljati ono što dopire samo do žlijezda, ali ne dopire do srca? Mediji nas svakodnevno bombardiraju austrijskim čudovištem Fritzlom, da spomenem samo jedan nečuven primjer. Od takve i slične pornografije nasilja i degradacije ne možemo ništa naučiti, niti nas ona može ganuti. Zar već ne znamo da je nedopustivo zatočiti, silovati, oploditi i mučiti vlastitu djecu? Da li takva i slične informacije uzvisuju ili zagađuju našu dušu? Čemu služe i kome koriste izvješća, iz minute u minutu, o osobnom životu bračnog para, koji su zapravo medijski klaunovi? Čemu nas oni mogu naučiti? Samo tome da su na ovome svijetu dvije stvari beskonačne, svemir i ljudska glupost. To već znamo, pa makar i samo intuitivno. Kako je svijet postao tako naheren? To me podsjeća na Solženjicinove riječi o vlastitu zatvorskom iskustvu i svijetu. Naime, on veli da ondje, na robiji, u njegovim mislima, vrijednostima i vizijama nije bilo dvosmislenosti, jer su misli bile skovane u zatvorskim ćelijama i po dugim marševima zaleđenim ravnicama - "provjerene TIM životom, nastale iz TAKVOG postojanja". Ali kad su izvanjski pritisci popustili i vidokrug se proširio, kad mu se najzad otkrio čitav svijet, ugledavši muljevitu močvaru, uzviknuo je: "Kako divna livada!" A za stup srama (s rupom za glavu zatvorenika) - reče: "Kakva krasna ogrlica!" I još kaže: "Ondje gdje su neki lijevali suze koje nitko nije mogao obrisati, drugi su plesali na melodiju bezbrižnog mjuzikla." Tu smo i mi danas. Solženjicin zaključuje kako mora postojati samo jedno mjerilo, jer ljudski rod ne može postojati sa šest, niti sa četiri, pa ni s dva mjerila vrijednosti; u protivnom rastrgat će nas nesuglasje ritmova, oprečnost vibracija. Čovjek sa dva srca nije za ovaj svijet, tako ne bismo mogli živjeti jedni uz druge na ovoj jednoj Zemlji. Stoga je moja želja i poruka onima koji budu čitali moje knjige, neka ih čitaju sa srcem, s jednim srcem, jer u životu uglavnom ne živimo sa jednim srcem, jer srce nema ideologije i ne može biti raskomadano. Ono suosjeća sa svima ili ne suosjeća ni sa kim. Zahvaljujem. Julienne Eden Bušić | Promotion of the book "Your Blood and Mine" by Julienne Eden Bušić, May 21, 2009, at the Mimara Palace in Zagreb I was with a lot of colorful characters in prison, and among them were the two nuttiest Charles Manson girls, Lynette Fromme and Sandra Good. They wore vests made out of Charlie's hair and did crazy things like bury the lawnmower so it wouldn't wake them up in the morning underneath their cell. Lynette tried to kill me one day with a claw hammer because I didn't want to be friends with her, but fortunately for me, the guards were nearby and I survived with a concussion, a bunch of stitches, and a good story to tell people whose lives are dull. So I'm obviously not a big fan of the Manson family. Nonetheless, I always liked the answer Charlie gave years ago to a journalist who asked him if he was crazy: "Man, I was crazy back when it meant something. Nowadays everyone is crazy." His answer is even more accurate today, but instead of everyone being crazy, now everyone is a terrorist. Ecology activists, abortion opponents, and even computer hackers, at least according to the US Department of Justice. What happened to the good old days, when there were real terrorists? The Red Brigade, for example, or the Red Army Faction. They actually intended to kill people, and they did, again and again, scores of them. Or Nelson Mandela, who openly advocated violence and led an organization responsible for hundreds of civilian deaths and bombings. And let's not forget all the state terrorism, from the Gulags to Goli Otok. Many of you in the audience tonight were victims of that, including Mr. Bilosnic. In more recent times we have Guantanamo, now fortunately in the process of disintegration. So although I give credit to the recent student strikers in Croatia - who would also be terrorists by some governments' definitions - they showed a lot of spirit and soul, they didn't need a lot of courage. In former Yugoslavia, they'd all be in prison, some would be tortured, and others might even die, and that's of course one of the reasons we hijacked a plane in 1976, to bring those kinds of crimes to the attention of the world, to force the Western, democratic press, who didn't care, to print our leaflets listing all the human rights violations, imprisonments, murders. But in contrast with the RAF, the Red Brigade, Nelson Mandela, and scores of others, I guess you could call us fake terrorists, because we did not advocate violence, and we tried to avoid instead of deliberately harm others. And the only death in our case was accidental, not intentional, and we will grieve it greatly the rest of our lives. By now some of you are probably asking yourselves if you've come to the wrong room. Isn't this supposed to be a book promotion? Shouldn't we be talking about the epistolary novel or the memoir genre, instead of unpleasant topics like terrorism? Yes, we should, in a rational world, but the fact is, I feel I have to first justify our right to be here, because an omnipresent gaggle of Croatian media commentators, self-proclaimed moral arbiters of the world, ostensible human rights activists, waspish authoresses in voluntary exile, the perpetual policemen, I call them, believe that those they consider terrorists have forfeited their right to associate freely in the world and to pursue their individual pursuits, to appear in public, to write books. So to them, I apologize. Here we are, in all our splendor! But can you really blame us? After all, we've taken heart in the fact that other real terrorists show their faces on a regular basis and seem not the least bit ashamed. Didn't the unrepentant Mandela recently celebrate his 90th birthday in London, greeting by 90,000 guests, including the British Prime Minister? And just last May, Karl Heinz Dellwo, former RAF terrorist or revolutionary, take your pick, was sharing his insights in Zagreb with the entire Croatia media, not so deep, not so profound: "there was violence, yes, but there was a concept behind it." Four people dead and all he had to say was that there was, after all, a "concept" behind it. For killing. He didn't mention how he felt about it, what he had learned, what he might teach others. All he did was repeat in his many media appearances the empty, disembodied political cliches of the time. Dellwo was released after serving only 20 years of two life sentences for the deaths of four people in Stockholm. The media should be silent, though, say the self-proclaimed moral arbiters, about Zvonko's homecoming after 32 long years, and our case in general, even if we had agreed to please them by disappearing, to be airbrushed from existence, like former dictatorships used to do to politicians that had fallen into disfavor. But let's think about the basic facts for a minute. A young and idealistic Croatian man undertakes a drastic hijacking to bring the world's attention to horrible human rights abuses, imprisonments, assassinations committed against his people, spends over half his life in prison, for these ideals, thereby paying his debt in full to society, his American wife who has no connection except love to a little place called Croatia, abandons her comfortable and, let's face it, pampered life to support her husband and also spends 13 years in prison, after which she waits loyally for him for 32 horrific years. I may be a little bit prejudiced, but that sounds like a story people might want to hear and read about, and perhaps, if these two people have looked deeply into their souls, can learn important lessons from. How does it feel to see the stars and moon for the first time after 20 years, as Zvonko did? How does one emotionally survive the very real possibility that a loved one will die in prison, as I did? How can one carry without complaint the guilt of others as well as one's own, as Zvonko did after 9-11? Love, guilt, passion, sacrifice, pride, joy, empathy…. where does one find the strength to endure profound suffering, what existential lessons can be learned, how can others broaden and enrich their lives through deep anguish, and was it worth the sacrifice? Even if it weren't our story, I would be interested in it. I would want to hear from such people, read about their experiences. Isn't that a normal reaction? Because what they have to say, if they can truly say it well, serves two functions, as literature of knowledge and literature of power, to teach and, more importantly, to move, as Thomas de Quincey postulated in his famous essay. Knowledge provides us with information, we know something concrete that we did not know before, and in our case, knowledge about our specific case, and not distortion and lies, is critical. But the literature of power seeks to move us, to exercise and expand our own latent capacity of sympathy with the infinite, where every pulse and each separate influx is a step upwards, and I am gratified to hear from so many people that they have been moved and even inspired by our words. Just imagine, for a moment, all the power that we would be deprived of if people who had committed illegal acts were banned, shunned, isolated, or prevented from speaking and writing of their experiences. Dostojevsky, Jean Genet, Vaclav Havel, Ezra Pound, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Oscar Wilde, and yes, even Nelson Mandela. The world would be a grim place without the words of Wilde in de Profundis: Many men on their release carry their prison about with them into the air, and hide it as a secret disgrace in their hearts, and at length, like poor poisoned things, creep into some hole and die. It is wretched that they should have to do so, and it is wrong, terribly wrong, of society that it should force them to do so. Society takes upon itself the right to inflict appalling punishment on the individual, but it also has the supreme vice of hallowness, and fails to realise what it has done. When the man's punishment is over, it leaves him to himself; that is to say, it abandons him at the very moment when its highest duty towards him begins. It is really ashamed of its own actions, and shuns those whom it has punished, as people shun a creditor whose debt they cannot pay, or one on whom they have inflicted an irreparable, an irremediable wrong. I can claim on my side that if I realise what I have suffered, society should realise what it has inflicted on me; and that there should be no bitterness or hate on either side. Or this, also by Wilde: " For us there is only one season, the season of sorrow. The very sun and moon seem taken from us. Outside, the day may be blue and gold, but the light that creeps down through the thickly-muffled glass of the small iron-barred window beneath which one sits is grey and niggard. It is always twilight in one's cell, as it is always twilight in one's heart". Yet instead of words of enlightenment, introspection, images to lift the human soul, the self-proclaimed moral arbiters repeatedly sneer at love, ignore saints, and build monuments to the decadent. Don't they comprehend that it is in vain to reiterate what reaches only the glands but not the heart? We are bombarded daily in the media about, to mention one egregious example, the Austrian monster Fritzl. We can neither learn nor be moved from that and similar pornography of violence and degradation. Don't we already know we shouldn't hold our children hostage, rape, impregnate, and torture them? Does that information elevate or contaminate our souls? Or minute by minute reports about the personal lives of two married media clowns. What can they teach us? Only that in this world, two things are infinite, the universe and human stupidity. We knew that already, if only by intuition. How did the world become so lopsided? It reminds me of what Solzhenitsyn wrote about his prison world, that there existed no ambiguity in his thoughts, values, and visions of the world, forged as they were in prison cells and long marches through the frozen plains, "tested by that life, growing out of that existence." But when the external pressures had fallen off and the horizon became broader, when the entire world finally revealed itself, he found it was a world that, upon seeing a slimy bog, exclaimed : "what a charming meadow!" And of a concrete pillory said : "what an exquisite necklace!" "Where some were shedding tears that could not be wiped away, there, others danced to the tune of a carefree musical." This is where we are today. His conclusion was that mankind cannot exist in the face of six, four or even two scales of values: we shall be torn apart by this disparity of rhythm, this disparity of vibrations. That a man with two hearts is not for this world, and neither shall we be able to live side by side on one Earth. So my wish tonight is that when you read my book, read it with one heart, and when you go about your daily lives, live it with one heart, because the heart has no ideology, and it cannot be broken into parts. It emphathizes with all or it emphathizes with none. Thank you. Julienne Eden Bušić |

| The presentation of the book "Your blood and mine" in the Mimara Palace in Zagreb has been accompanied by deeply moving address of Mr. Zvonko Bušić. He closed his address by reciting by heart the following verses written by Konstantin Simonov, which according to his own words perfectly reflect his personal life story. The original Russian title of the poem is Zhdi menja, in Croatian Čekaj me, and in English Wait for me.

|

| Official website for Zvonko and Julienne Busic, in English and Croatian: Letters from the trial Judge, interviews, articles, commentaries, documents (US State Department, US Parole Commission, etc.), photos, links, etc. |

Formated for CROWN by prof.dr. Darko Žubrinić

Distributed by www.Croatia.org . This message is intended for Croatian Associations/Institutions and their Friends in Croatia and in the World. The opinions/articles expressed on this list do not reflect personal opinions of the moderator. If the reader of this message is not the intended recipient, please delete or destroy all copies of this communication and please, let us know!