Premio Brajnovic a la communication is a prestigious Spanish award (500,000 pesets) established in 1997 upon the initiative of newspapermen and lecturers from the University of Pamplona as a recognition to Luka Brajnović (born in 1919 in Kotor, in Boka kotorska in today's Montenegro, died in 2001). He was a professor of Ethics of the University of Navarra, a former director of the Institute of Artes Liberales, a well known Spanish intellectual. It is interesting that the award was established during his lifetime.

Professor Brajnovic on the right, Prof. Radovan Grgec, Mrs Brajnovic,

and the King of Dolls on the left, in Pamplona (many thanks to Prof. Grgec) He was the founder and the dean of the prestigious School of Communication at the Universtiy of Pamplona (Facultad de Comunicación de la Universidad de Navarra) until his retirement, and he educated hundreds of top newspapermen working in Spain and in Latin America.Luka Brajnovic is the author of important monographs, like

- Deontologia periodista,

- Literatura de la revolucion bolschevique,

- Despedidos y encuentras,

- Tecnologia de la informacion.

Professor Brajnovic had to escape from Croatia in 1945 in front of the Yugoslav communist threat. He also collaborated intensively with various Croatian emigrant journals.

- One of his brothers was killed by Yugoslav partisans on the islet of Daksa near Dubrovnik in 1944, sharing the same destiny as the whole group of forty four leading Dubrovnik intellectuals.

- Premio Brajnovic for 2001 was conferred posthumously to Sinisa Glavasevic, Croatian newspaperman killed in Vukovar in 1991 during the Greater-Serbian aggression on Croatia. Exhumed from the mass grave Ovcara near Vukovar together with several hundred detainees from the city hospital.

- Premio Brajnovic for 2005 was conferred to Dr. Joaquin Navarro-Valls, director of The Holly See Press Office, The Vatican. It is interesting that he studied among others at the Faculty of Sciences and Communication in Pamplona where Luka Brainovic was teaching.

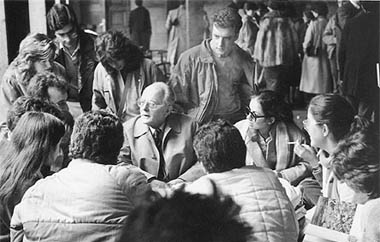

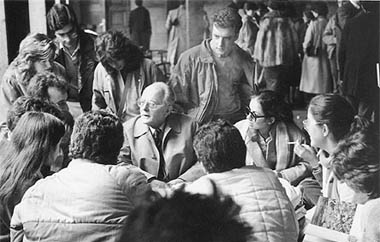

Photo from Faculdad de Comunicacion (School for Communication)

Universidad de Navarra |

The Luka Brajnovic Award for Communication was inaugurated by the School of Communication at the University of Navarra in 1997. The award was established in memory of Luka Brajnovic (who died on the 8th February 2001) as a mark of respect to his career, his professional standing and reputation. Journalist, writer and Croatian poet resident in Spain after World War II, Luka Brajnovic was professor of more than thirty generations of journalists in the University of Navarra and first author of an Information Deontology manual written in Spanish. The Award is bestowed on those who have defended human dignity and the fundamental values of freedom, tolerance and solidarity in their work in the field of communication. Thus far, the award has been granted to the following people: - 1997: Miguel Delibes, writer and journalist.

- 1998: Violeta Chamorro, former President of Nicaragua.

- 1999: David Puttnam, British film producer.

- 2000: Antonio Fontán, journalist and professor of journalism.

- 2001: Sinisa Glavasevic, Croatian journalist.

- 2002: Medios para la Paz, a Colombian media organization.

- 2003: José Javier Uranga, Navarre journalist.

- 2004: Ettore Bernabei, Italian TV executive and producer.

- 2005: Joaquín Navarro-Valls, spokesperson for the Holy See.

- 2006: Krzysztof Zanussi, Polish director and producer of cinema.

Don Luka, my professor, by Carmen Ripa | | | PROFESSOR | | |

Don Luka, my professor By Carmen Ripa

Starting university studies at the age of sixteen involves discovering a new sense of freedom, independence and responsibility. For me personally, going to the university, in my case, the University of Navarra, was a sea change. I was on my own for the first time, a student of journalism, full of expectation, the happiest woman in the world. Everything was as I had imagined it would be. Everything, that is, except Don Luka, the most outstanding professor in Pamplona, although he wasn´t from Pamplona. Don Luka Brajnovic was born in Croatia and had been the editor of a newspapeer. Nothing in his quiet demeanor gave away the fact that he missed his country or that he had suffered greatly. He never spoke of his inner feelings, but his daughter, Elica, was a friend of mine and one day she showed me a photograph of her little sisters and brother. When I commented on how young they were, Elica explained that she hadn´t met her father until she was thirteen: �It was in 1956 at the train station in Munich where I saw him for the first time waiting for my mother and me as we stepped onto the platform. My father had escaped from Yugoslavia and had wandered around Europe and he had even been confined to a concentration camp. My mother hadn´t seen him again since I was born.ar I wasn´t able to get accustomed to the idea that that thin man was my father. Since then, Munich is the most wonderful city in the world. Afterwards, here in Spain, the family grew.� There was no trace of sadness in Don Luka´s eyes, only peace of mind. His classes were tranquil, calm, serene. I learned a lot from him, both personally and professionally, because, as he said, �a media professional is one who dedicates himself to the service of others�. He taught us in such a manner as to make us want to learn, not just to pass examinations. That passing an examination was a momentary victory, but learning in itself was for a lifetime. That no one should feel ashamed of a failing grade. Incredible as it may seem, I discovered that there were any number of historically significant men and women, including some Nobel Prize winners, who had received failing grades. Ramon y Cajal had failed Logic and Psychology; Ramon del Valle-Inclan was hopeless in Latin; Castellano in Arithmetic, Algebra and International Law; Garcia Lorca failed Spanish Language five times; Azorín, General Literature and Spanish Literature; Ramon de la Serna, Literature; Pio Baroja, three failing grades in Pathology and Spanish Poetry; Machado, Eduardo Marquina and Ramon Jimenez failed in Critical History of Spain. No problem there. Learning is what is important in life. Don Luka has left and gone to heaven, leaving behind a portion of his wisdom and learning, and the example of the goodness of his heart that never transmitted an ounce of hatred. And forgiveness. I have taken to heart a comment he once made which reflects hispersonality; �every day of my life I have struggled in a positive manner against hatred�. He was always Don Luka, perhaps because we never spoke informally to our professors, or maybe because he was simply a great man. Goodbye Don Luka. |

|

Luka Brajnovic among his students in Pamplona, Spain (source) |

Luka Brajnovic Davinovic was born in Kotor, Croatia, in 1919. He studied law in Zagreb, and was president of the League of Croatian Students. When Communism took over his country, he was persecuted for the faith and risked his life with Christian heroism on various occasions. He was forced to leave his country and spent twelve years without being able to see his wife and daughter. He managed to reach Italy, where he met Blessed Josemaria. He later moved to Spain, and resided there until the end of his life. He joined Opus Dei in 1952. In 1960 he became a professor in the School of Journalism at the University of Navarre. He was noted for his simplicity, good humor and spirit of service. He died in Pamplona on February 8, 2001. Source

|

|