The Sarajevo Film Festival was enraptured by a Cannes-winning film by Bosnian director Danis Tanović. Ilya Marritz witnessed the event and caught up with the director.

| SARAJEVO FILM FESTIVAL

|  |

Danis Tanović admits he was tense on the warm August night when 2700 filmgoers crowded into an enormous courtyard in central Sarajevo to watch the hometown debut of his film. Tanović is the author and director of No Man's Land (2001), a feature that had recently won the Best Screenplay award at Cannes and which was selected to open the 7th Sarajevo International Film Festival this year. The buzz surrounding the film was considerable, and, with reason, Tanović is not given to modesty. Still, the showing of the film in Sarajevo was a singular occasion.

"I was rather excited, even more so than when I was in Cannes," said Tanović. "Here, people have been expecting [the film] for two months and the whole thing kept pumping up more and more and very often when you have this kind of situation, often things just blow up."

"[These people] lived through the war. As this is a war story, they have an eye which sees in much more detail and they pay attention to each little detail they see," noted the director, "so they were really a hard public and I think if I survive this, I'm gonna survive any other premiere."

Fiction that is true to life

Tanović didn't merely survive the premiere, he triumphed. Nearly every audience member I spoke with after the screening spoke glowingly of No Man's Land , praising it for its clever plot and realistic depiction of the war. Many people felt that No Man's Land is special because it is the first film to show the Bosnian war "as it really happened." Strictly speaking, Srđan Dragojević's grisly Lepa sela lepo gore (Pretty Village, Pretty Flame, 1996) might be a truer graphic depiction of the ghastliness of war. But what is really remarkable about No Man's Land is the way Tanović successfully reduces the entire cast and breadth of the Bosnian war to a few characters in and around a little foxhole between the Bosnian and Serb frontlines. Without resorting to stock characters or clichés, Tanović’s drama unfolds—a Catch-22 updated for the media age.

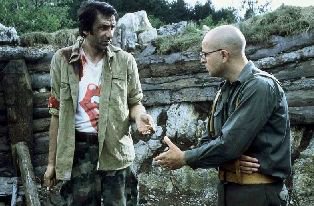

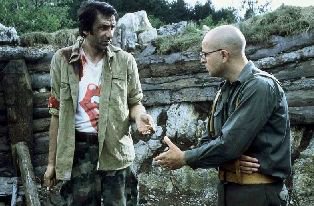

No Man’s Land is the story of three soldiers in an absurd fix. They are Čiki (the beloved Bosnian comic actor Branko Đuric, making a comeback in his native country), Cera (Filip Šovagović) of the Bosnian Army, and Nino (Rene Bitorajac), a fresh Serb recruit. While on a scavenger mission following a skirmish between Serb and Bosnian units, Nino and his commander search a trench for cigarettes or any remaining Bosnian soldiers still hanging on to life. As a joke, Nino's idiotic senior commander drags what he believes to be a dead body over a jumping mine—an insidious device that won't detonate until his comrades eventually come to retrieve his body. From a nearby hiding place, Čiki watches on in disgust. He guns down the Serb commander a few seconds later, letting Nino get by with only a wounded leg.

|

| Nino extends a hand to a relucant ally |

Tanović relies heavily on humor to defuse the tension and highlight the ironies of the situation. When, in a scene set a few hundred meters away from the trench, one soldier puts down his newspaper and shakes his head, telling the second soldier that things are getting really bad in Rwanda, the audience roared at the joke. Inside the trench, Čiki and Nino sometimes seem like squabbling brothers. Čiki compels Nino at gunpoint to admit his side's guilt in the war. When the tables are turned minutes later and Nino has a gun and Čiki doesn't, Nino, with a wry smile, extracts the same admission of guilt from Čiki. Again, the audience guffawed.

"I often say that this is a serious film with a good sense of humor," said Tanović. "I didn't want to make a film that is very tough to watch and that nobody wants to go see. I wanted to make a film which is tough but which everybody will go to see."

A foreign production, but a Bosnian result

|

| The media home in on a good story |

A French-Belgian-Italian-Slovenian co-production, No Man's Land wasn't even filmed in Bosnia—it was shot in Slovenia and Italy—but it will be Bosnia's submission for Oscar consideration this year and is indubitably more "Bosnian" than anything else. The enthusiasm generated by the film in Bosnia is reflective of the satisfaction Bosnians feel for at last gaining recognition for their cultural achievements—even when those achievements relate directly to the war that made their country infamous.

Probably no one feels this satisfaction more than the Director of the Sarajevo Film Festival, Mirsad Purivatra. "Culture is usually the last on the list [of areas] supported by the government and it's not so easy," said Purivatra, who is in his second year as Festival Director, also noting that:

Danis has already produced very good energy among young filmmakers. It was so important to show young filmmakers that, in spite of the lack of support [from Bosnia's government], the film could be made. I think he made a great picture of Bosnia, and I think also a very important picture. We will see this, I think, in the coming years as a big antiwar film but also [a film that has] very strong opinions regarding the facts about some of the people who started the war.

A film about his people, a story for the world

|

| Speaking in plain language |

In contrast to Callow's character, the hapless, bespectacled Nino—who early on extends his hand to Čiki, only to be disdainfully rebuffed—lacks the general's extreme jadedness. Content as he is to be fighting on the Bosnian Serb side, Nino is a pleasant enough picture of Serbian moral indifference. There are, of course, a few jokes at the expense of Serbs—including some cheap homophobic humor—but Tanović's personal bitterness about the war really only becomes apparent when you speak with him in person.

|

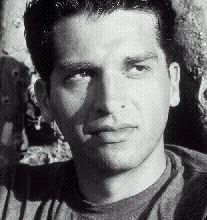

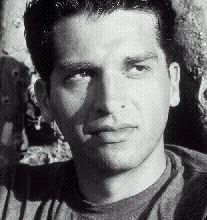

| Director Danis Tanović |

Encouraged by his reception at Cannes, and now in Sarajevo, Tanović is optimistic about his film's chances to reach a wider audience:

I think I managed [to make my point], because after the Cannes projection, there were some people coming to me from Bangladesh who just told me, "You know, we have the same kind of problems in our country. And there were some people from Pakistan who were saying he same things. And then the Japanese went to see the film, and MGM/United Artists bought it. So you know, I think everybody understood the message.

They certainly understood it on opening night in Sarajevo. After the screening, however, many filmgoers were shocked to hear a series of ear-shattering explosions above them. Their fears were allayed when they looked up and saw a beautiful fireworks show. Perhaps not a tasteful tribute, but a fitting one—and a powerful reminder of the simple pleasure of being able to sit outside on a warm summer night and watch a good feature film.

| SARAJEVO FILM FESTIVAL The Sarajevo Film Festival was enraptured by a Cannes-winning film by Bosnian director Danis Tanović. Ilya Marritz witnessed the event and caught up with the director.

|  |

Danis Tanović admits he was tense on the warm August night when 2700 filmgoers crowded into an enormous courtyard in central Sarajevo to watch the hometown debut of his film. Tanović is the author and director of No Man's Land (2001), a feature that had recently won the Best Screenplay award at Cannes and which was selected to open the 7th Sarajevo International Film Festival this year. The buzz surrounding the film was considerable, and, with reason, Tanović is not given to modesty. Still, the showing of the film in Sarajevo was a singular occasion.

"I was rather excited, even more so than when I was in Cannes," said Tanović. "Here, people have been expecting [the film] for two months and the whole thing kept pumping up more and more and very often when you have this kind of situation, often things just blow up."

"[These people] lived through the war. As this is a war story, they have an eye which sees in much more detail and they pay attention to each little detail they see," noted the director, "so they were really a hard public and I think if I survive this, I'm gonna survive any other premiere."

Fiction that is true to life

Tanović didn't merely survive the premiere, he triumphed. Nearly every audience member I spoke with after the screening spoke glowingly of No Man's Land , praising it for its clever plot and realistic depiction of the war. Many people felt that No Man's Land is special because it is the first film to show the Bosnian war "as it really happened." Strictly speaking, Srđan Dragojević's grisly Lepa sela lepo gore (Pretty Village, Pretty Flame, 1996) might be a truer graphic depiction of the ghastliness of war. But what is really remarkable about No Man's Land is the way Tanović successfully reduces the entire cast and breadth of the Bosnian war to a few characters in and around a little foxhole between the Bosnian and Serb frontlines. Without resorting to stock characters or clichés, Tanović’s drama unfolds—a Catch-22 updated for the media age.

No Man’s Land is the story of three soldiers in an absurd fix. They are Čiki (the beloved Bosnian comic actor Branko Đuric, making a comeback in his native country), Cera (Filip Šovagović) of the Bosnian Army, and Nino (Rene Bitorajac), a fresh Serb recruit. While on a scavenger mission following a skirmish between Serb and Bosnian units, Nino and his commander search a trench for cigarettes or any remaining Bosnian soldiers still hanging on to life. As a joke, Nino's idiotic senior commander drags what he believes to be a dead body over a jumping mine—an insidious device that won't detonate until his comrades eventually come to retrieve his body. From a nearby hiding place, Čiki watches on in disgust. He guns down the Serb commander a few seconds later, letting Nino get by with only a wounded leg.

|

| Nino extends a hand to a relucant ally |

Tanović relies heavily on humor to defuse the tension and highlight the ironies of the situation. When, in a scene set a few hundred meters away from the trench, one soldier puts down his newspaper and shakes his head, telling the second soldier that things are getting really bad in Rwanda, the audience roared at the joke. Inside the trench, Čiki and Nino sometimes seem like squabbling brothers. Čiki compels Nino at gunpoint to admit his side's guilt in the war. When the tables are turned minutes later and Nino has a gun and Čiki doesn't, Nino, with a wry smile, extracts the same admission of guilt from Čiki. Again, the audience guffawed.

"I often say that this is a serious film with a good sense of humor," said Tanović. "I didn't want to make a film that is very tough to watch and that nobody wants to go see. I wanted to make a film which is tough but which everybody will go to see."

A foreign production, but a Bosnian result

|

| The media home in on a good story |

A French-Belgian-Italian-Slovenian co-production, No Man's Land wasn't even filmed in Bosnia—it was shot in Slovenia and Italy—but it will be Bosnia's submission for Oscar consideration this year and is indubitably more "Bosnian" than anything else. The enthusiasm generated by the film in Bosnia is reflective of the satisfaction Bosnians feel for at last gaining recognition for their cultural achievements—even when those achievements relate directly to the war that made their country infamous.

Probably no one feels this satisfaction more than the Director of the Sarajevo Film Festival, Mirsad Purivatra. "Culture is usually the last on the list [of areas] supported by the government and it's not so easy," said Purivatra, who is in his second year as Festival Director, also noting that:

Danis has already produced very good energy among young filmmakers. It was so important to show young filmmakers that, in spite of the lack of support [from Bosnia's government], the film could be made. I think he made a great picture of Bosnia, and I think also a very important picture. We will see this, I think, in the coming years as a big antiwar film but also [a film that has] very strong opinions regarding the facts about some of the people who started the war.

A film about his people, a story for the world

|

| Speaking in plain language |

In contrast to Callow's character, the hapless, bespectacled Nino—who early on extends his hand to Čiki, only to be disdainfully rebuffed—lacks the general's extreme jadedness. Content as he is to be fighting on the Bosnian Serb side, Nino is a pleasant enough picture of Serbian moral indifference. There are, of course, a few jokes at the expense of Serbs—including some cheap homophobic humor—but Tanović's personal bitterness about the war really only becomes apparent when you speak with him in person.

|

| Director Danis Tanović |

Encouraged by his reception at Cannes, and now in Sarajevo, Tanović is optimistic about his film's chances to reach a wider audience:

I think I managed [to make my point], because after the Cannes projection, there were some people coming to me from Bangladesh who just told me, "You know, we have the same kind of problems in our country. And there were some people from Pakistan who were saying he same things. And then the Japanese went to see the film, and MGM/United Artists bought it. So you know, I think everybody understood the message.

They certainly understood it on opening night in Sarajevo. After the screening, however, many filmgoers were shocked to hear a series of ear-shattering explosions above them. Their fears were allayed when they looked up and saw a beautiful fireworks show. Perhaps not a tasteful tribute, but a fitting one—and a powerful reminder of the simple pleasure of being able to sit outside on a warm summer night and watch a good feature film.